A lot of us can probably name a ballet. Swan Lake, The Nutcracker and Sleeping Beauty are some of the most common answers I get when I tell people I’m interested in ballet- I’ve also gotten Giselle, and Anna Pavlova’s Dying Swan. But there are plenty of ballets that have fallen by the wayside, some for good reason.

In the late 1830s the Paris Opera Ballet was in the middle of its Romantic Period. Surviving works from this era (though not in their original form) include La Sylphide (1832), in which leading ballerina Marie Taglioni triumphed, and Giselle, one of the classics, created for Carlotta Grisi in 1841.

However there are quite a few ballets from this era that haven’t survived, including the one I’d like to focus on today: Le chatte métamorphosée en femme, which premiered on 16th October 1837.

Paris, 1837

La chatte métamorphosée en femme translates roughly to The cat metamorphosed into the woman, or The cat transformed into the woman. It may conjure up images of Swan Lake, or The Princess and the Frog, but there was no transforming into anything at all. Just a plan to pretend to.

The scenario (story) was developed by Charles Duveyrier (1803-1866). Duveyrier was the younger brother of the playwright Mélesville (1787-1865), and as far as we know wrote no other ballets for the Paris Opera Ballet. Not a great sign.

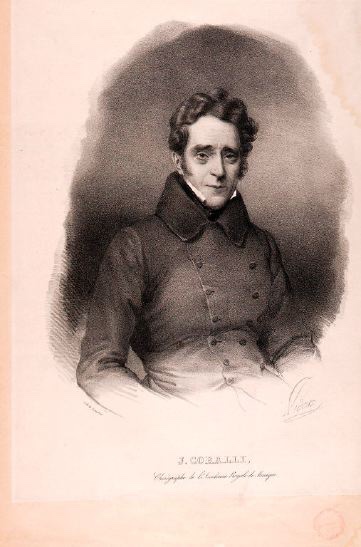

The choreographer, on the other hand, was more celebrated. Jean Coralli (1779-1854), had trained at the Paris Opera’s School of Dance, and choreographed in Vienna, Milan, Marseille, Lisbon, and, from 1824-1829, at the Théâtre de la Porte-Saint-Martin. He was hired as premier maître de ballet at the Paris Opera in 1831, and would continue in the role until 1850. His most well known ballet today is Giselle (a collaboration with Jules Perrot), but his other successes included Le Diable Boiteux (1836), La Tarentule (1839) and La Péri (1843).

Four people are credited with designing La Chatte. These four are Monsieurs Pourchet, Devoir, Philastre and Cambon. The last two named seem to be the most well known, as they were employed as designers at the Paris Opera from around 1835. Among their ballets were Brézilia, ou la Tribu des femmes (1835), Le Diable Boiteux (1836), La Gipsy (1839), La Tarentule (1839), La Péri (1843), Paquita (1846) and Nisida (1853).

After this Philastre seems to either have died or retired, and Cambon continued designing ballets up until 1870, his final credit being for Coppélia. This may or may not indicate a death in the Siege of Paris, which lasted from 19th September 1870 to 28th January 1871. Monsieurs Pourchet and Devoir are only credited for one other ballet, Les Mohicans, which premiered months before La chatte and was in repertory for a incredibly short time: 2 performances.

And then, of course, there are the dancers. The ballet was led by Fanny Elssler (1810-1884) and Joseph Mazilier (1801-1868). Mazilier had joined the Paris Opera in 1830, and would not only dance, but also choreograph. His ballets include La Gypsy (1839), Le Diable amoureux (1840), Le Diable à quatre (1845), Paquita (1846) and Le Corsaire (1856). As a dancer, he’d originate the roles of James in La Sylphide (1832), Rudolph in La Fille au Danube (1836) and Luigi in La Tarentule (1839).

Fanny Elssler first appeared at the Paris Opera in 1834. At the time the leading ballerina was Marie Taglioni, noted for her pointe work and jumps. Contrasting with Taglioni was Elssler, who was more grounded and earthly, focusing on precision and smaller steps in quick succession. Her most famous dance was La Cachucha, which was featured in Corelli’s Le Diable Boiteux (1836). Though she was Austrian, Elssler became known for this Spanish National Dance, which she would perform frequently hereafter. The Cachucha was being performed in Paris at the time by Spanish dancer Dolores Serral; Elsser brought a classical education to the national dance, and sparked a craze.

Back to La Chatte. Supporting roles in the ballet were performed by Jean-Baptiste Barrez (1792-1868), Germain Quériau (1790-1850), Conard Florentine and Maria Jacob (fl.1836-1849). All round this was a rather star-studded cast, building the anticipation for the ballet. Sadly, it wouldn’t live up to the hype.

The Plot

The ballet is based on a vaudeville, written by Eugène Scribe and Monsieur Duveyrier’s older brother Mélesville in 1827. Scribe was writing ballet scenarios at the time, so one has to wonder why he didn’t adapt his own work. But the original version was set in Germany; 1837’s version was set in China. And the main character’s name is Oug-Lou. Yes, really. Oug-Lou.

We follow Oug-Lou (Mazilier), who lives in a solitary cabin with one old servant Kan-koi (Florentine), and adores his cat. He catches the eye of Princess Kié-li (Elssler). Kié-li contrives a situation for him to rescue her, and then invites him to the palace. He goes to the fête at the palace, but leaves at the end with Kan-kou and the cat, which upsets Kié-li, as she had expected him to stay.

Kié-li’s tutor Kiang-sse-Long (Barrez), who is in on the whole operation, makes up a spiel about a dragon coming to engulf the Kingdom (this is apparently an solar eclipse). He declares that Kié-li must stay on her throne in the darkness, and in the morning, the first man she sees she will marry. He manages to get Oug-Lou to her side; in the morning, he is the first man she sees. When he refuses to marry her, the Emperor (Quériau) banishes him.

In Act 2 (stay with me, this is 3 Acts), Kiang-sse-long gives Oug-Lou, who has been banished to a forest, a bonnet that will turn his cat into his dream woman. When he goes to transform his cat, Kié-Li appears, and pretends to be his cat. Oug-Lou is overjoyed. Kié-Li, who’s brilliant plan this was, acts like a cat to prove that cats are annoying, and to show him that what he really should adore are women. He’s not convinced.

Kié-Li’s plan falls apart when the real cat appears. The real cat had been sold by Kan-kou to one of the Emperor’s Pages (Maria). Somehow the cat manages to escape and return to Gou-Lou. Kié-Li then gives up, tells him everything, and they end up getting married.

This might sound like a bit of a mess. That’s because it was. There’s obvious flaws in the plot, and one must wonder whether anyone in the auditorium was able to watch it with any willing suspension of disbelief. Paris’ top dance critic, Théophile Gautier, certainly didn’t.

Gautier’s Review

Théophile Gautier (1811-1972), wrote lots of things. Novels, poem, criticism, ballets. He’s known by me for the latter two. As a scenarist he wrote Giselle (1841), La Péri (1843) and Pâquerette (1851). As a critic, he was an ardent defender of the Romantic Ballet, and is considered to be one of the greatest dance critics of all time. But he was harsh on Le chatte. Ivor Guest compiles this review, originally written by Gautier for Le Presse on 23rd October 1837, in his 1986 collection Gautier on Dance.

Gautier would crown the ballet with the new name Le Lapin blanc métamorphosée en femme. Le Lapic blanc means the white rabbit, and refers to the fact that the ‘cat’ used in the ballet was really a stuffed rabbit. In fact, halfway through his review he just starts referring to the cat as the rabbit.

He describes the scenery with similar disdain. The solar eclipse was presented by covering ‘the sun’ with black sealing wax. The sun itself looked somewhat like a fried egg.

The scene changes to reveal, according to the scenario, a vast amphitheatre in the Emperor’s Palace. We give the scenario’s definition in default of any other, for we were never able to discover for ourselves what the stage was supposed to represent.

Théophile Gautier, La Presse, 23rd October 1837

He also points out the flaws in the plot. Mainly, why would a man who’s primary obsession is his cat be overjoyed to find out he could turn his cat into a woman? Surely if he’s happy with the cat it’s because he wants the cat, not a woman. There’s plenty of them out there. But, to quote Gautier ‘the ballet does not bother itself with such details’.

Gautier highlights the fact that Kié-Li’s plans don’t make much sense. This can be explained away in most arts forms, including ballet, if it’s done well enough. For example in Giselle, produced only 4 years later, Giselle and Albrecht have already met each other, making the whole thing easier to believe. But from Gautier’s review, and a plot summary by Ivor Guest, I can only infer that Kié-Li and Oug-Lou have never seen much of each other at all. At least most fairytales have a quest. This ballet just has an elephant for Kié-Li to fall off (which was seemingly played by a horse).

…how does one manage to be carried off to a prearranged spot and know that a man named Oug-Lou, who is passionately in love with his cat, will be standing just there by the roadside to perform the rescue?

Théophile Gautier, Le Presse, 23rd October 1837

The one good thing Gautier finds about the ballet is the performance of Elssler, a consistent in all his reviews. At this time ballerinas was deemed more important than male danseurs, and had more actual dancing to do. In fact Gautier commends a ballet (La Volière, 1838, choreographed by Fanny’s sister Therese) in a later review for giving the men no actual dancing, just mime. He is also a champion of Elssler’s talent, writing appreciation pieces about her, and refers to her as a ‘Pagan ballerina’, in contrast to Marie Taglioni being seen as the ‘Christian ballerina’.

How much nicer it would have been for both us and our readers if we had talked about Mlle Elssler, who was as charming as ever and displayed a real cat-like suppleness in the pas that was added at the second performance! The frightful inadequacy of the plot could not have been more gracefully concealed.

Théophile Gautier, La Presse, 23rd October 1837

All was not lost. There was some joy to be found in this ballet. No sources commend or critique the music, but considering Gautier calls the performance of the ballet as a whole boring, it can’t have been much to write home about.

So why is it forgotten?

As you can probably guess from Gautier’s review, the ballet wasn’t great. It didn’t live up to the anticipation the casting (particularly Elssler) had brought it. While it doesn’t seem to be that detached from Romantic Ballet as a whole plot-wise, it is one of the more noticeable failures.

From a modern standpoint, reading the scenario, it seems like the boring aspect was why it failed. I think an audience would’ve been able to overlook the plot if the scenery, choreography and music had been good enough. But, as Gautier’s review shows, Elssler carried the majority of the ballet on her shoulders, and that’s not what we should want from a 3-Act ballet.

The ballet was only in the repertoire for one year, 1837. And considering it premiered in mid-October, that’s not good news.

Ivor Guest gives the number of performances of La Chatte at 16. It’s certainly not the worst; there were a number of ballets during the Romantic Period that managed less than 16:

- Le fête hongroise (1821) holds the record, with a grand one performance. It was a divertissement by Jean-Pierre Aumer, and featured himself, Paul and Madame Anatole in the lead roles

- Le Sicilien, ou l’Amour peintre (1827), a 1-Act ballet by Anatole Petit [Madame Anatole’s husband], managed 6. It would’ve been wholly forgettable if not for the fact that Marie Taglioni made her debut in one of those six performances.

- Brézilia, ou la Tribu des femmes (1835) was designed by La Chatte’s Philastre and Cambon. Choreographed by Filippo Taglioni [Father of Marie], it featured Marie Taglioni, Amelia Legallois, Pauline Leroux and Mazilier. It got 5 performances

- The other two designers, Devoir and Pourchet, contributed to Les Mohicans (1837), which got two. It featured Nathalie Fitzjames in the lead role.

- Therese Elssler’s 1-Act ballet La Volière, ou les Oiseaux de bocces (1838) was first produced for a benefit performance of Fanny Elssler. It got 4 performances.

- Another Jean Coralli ballet from 1844, Eucharis, received 6 performances. Featured in the ballet were Adèle Dumilâtre, Pauline Leroux and Lucien Petipa.

- Lastly, Ozai (1847), got 10 performances, being another Coralli ballet that didn’t leave a mark.

La Chatte takes its place among these ballets (some of which might also be featured in these series) as one of the worst received ballets of the Romantic Period. There are some ballets that historians like me wish they could’ve seen, but this one would’ve been watched once for the novelty and then promptly abandoned. Which might’ve been why it only lasted 16 performances.

Sources

Beaumont, Cyril W. (1956). The Complete Book of Ballets. Putnam, London, England.

Gautier, Théophile & Guest, Ivor (translation) (2012). Gautier on Dance. Noverre Press, Hampshire, England.

Guest, Ivor (2006). The Paris Opera Ballet. Dance Books Ltd, Alton, England.

Guest, Ivor (1966). The Romantic Ballet in Paris. Pitman & Sons, London, England.