Choreographer George Balanchine was a genius. There’s no denying that. His musicality and neoclassical style have influenced countless other choreographers, and his works are performed all around the globe.

But that’s not to say all of his ballets are remembered. Balanchine defected from the Soviet Union in 1924 and worked with the Ballet Russes for the next few years. After the death of the Russes’ impresario Sergei Diaghilev in 1929, he worked with the Royal Danish Ballet and a few of the Ballet Russes’ smaller successors. He travelled to America in 1933, opening a ballet school the next year. And the rest, they say, is history.

Today I’d like to look at one of the ballets Balanchine created while he was with the Ballet Russes: The Triumph of Neptune, premiered on the 3rd December 1926 at the Lyceum Theatre, London.

The Ballet Russes

The Ballet Russes first performed in Paris, in 1909. Sergei Diaghilev had gathered together a group of Russian dancers to perform during the Summer. Among the dancers during the early seasons were Tamara Karsavina, Vaslav Nijinsky, Bronislava Nijinska, Anna Pavlova and Mikhail Fokine.

The Ballet Russes started in Paris, but frequently danced in London as well. At the time ballet in England was based at the Empire Theatre and the Alhambra Theatre, with a few dancers appearing in the Operas at Covent Garden. The Ballet Russes’ arrival in London, combined with Adeline Genée’s efforts at the Empire, boosted ballet in England.

The Troupe was initially a Summer one, performing during the off-season of the ballet companies in Russia. But Diaghilev was persistent, and the outbreak of World War One combined with the Russian Revolution meant a lot of his dancers had more time to devote to him.

It was in late 1926 that Ballet Russes appeared at the Lyceum Theatre, for a ‘popular season’. As you might be able to guess ‘popular’ could be a synonym for pandering to the public. The season was sponsored by Lord Rothermere, who was a founder of the Daily Mail, and would later be an open supporter of fascism and the Nazi party. According to dancer Tamara Geva, he also had a mistress who danced with the Russes. There must’ve been a very, interesting, dynamic at the Lyceum in late 1926.

While the new ballets the Ballet Russes presented weren’t necessarily as influential as the earlier ones, they were still the Ballet Russes. And that combined with Diaghilev’s persistence meant people would flock to dance with them.

The Cast

Throughout their lifespan the Ballet Russes’ ballets had very accomplished casts. And The Triumph of Neptune was no different. Cyril W. Beaumont lists some of the cast in his book The Complete Book of Ballets.

- Alexandra Danilova as The Fairy Queen. Danilova (1903-1997) trained at the Imperial Ballet School alongside Balanchine, and would later defect alongside him in 1924. After Diaghilev’s death she danced with the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, becoming a sensation as the Glove-Seller in Léonide Massine’s Gaîté Parisienne. She would collaborate with Balanchine on a staging of Coppélia for the New York City Ballet, in 1974.

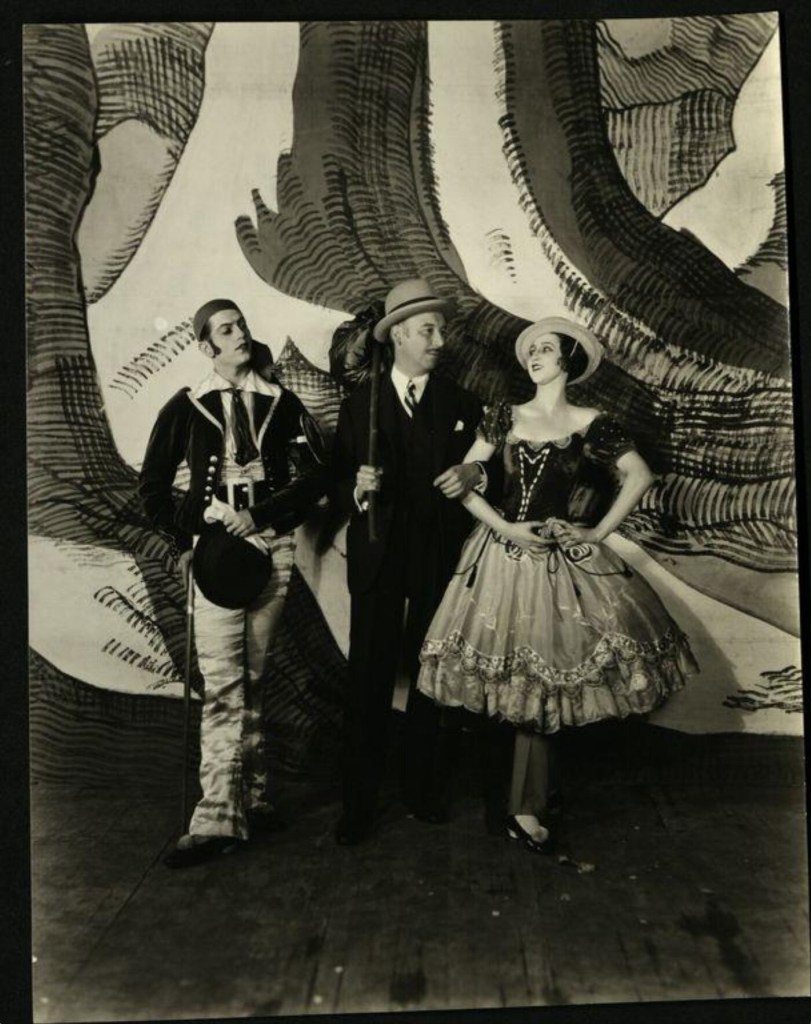

- Serge Lifar as Tom Tug, a Sailor. Known as one of the greatest dancers of the century, Lifar (1905-1986) studied with Bronislava Nijinska, and made his Ballet Russes debut in 1923. Other Balanchine roles he originated included the titular roles in Apollo (1928) and The Prodigal Son (1929). He’d later become the maître de ballet of the Paris Opera Ballet from 1930-1944, and 1947-1958.

- Mikhail Fedorov as W. Brown, a Journalist. Fedorov was the younger brother of Sofia Federova (1879-1963), another Ballet Russes dancer. He also danced in the premiere of The Prodigal Son, as the titular character’s Father.

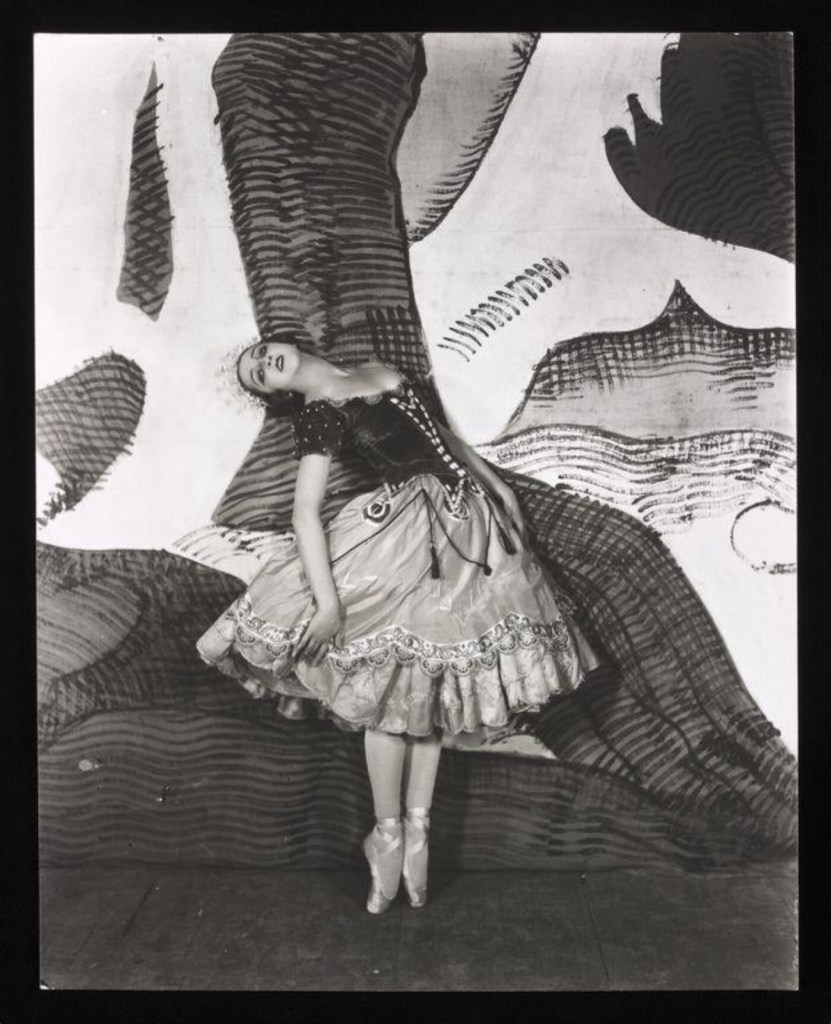

- Lydia Sokolova as The Goddess. Sokolova (1896-1974) was an English Ballerina (born Hilda Tansley Mussings) who trained under the likes of Anna Pavlova and Enrico Cecchetti. She joined the Ballet Russes in 1913, remaining with the company until 1929. She originated parts in La Boutique Fantasque (1919, as a Tarantella dancer), and Les Matelots (1925, as the Heroine’s Friend).

- Vera Petrova and Lubov Tchernicheva as Fairies and Sylphs. While I have less on Petrova, both these dancers seem to be Imperial trained. Tchernicheva graduated in 1908, and Petrova in 1913. Tchernicheva’s originated Ballet Russes roles include The Queen of Clubs in La Boutique Fantasque (1919), Prudenza in Pulcinella (1920) and one of the Two Ladies in The God’s Go A-Begging (1928).

- Tatiana Chamie as The Street Dancer. Another Russian trained dancer, Chamie danced with the Ballet Russes, and then with the Original Ballet Russe. She originated a role in the Rondeau of Bronislava Nijinska’s Les Biches (1924).

- Tatiana Barasch as The Sailor’s Wife. Barasch graduated from the Imperial Ballet School in 1918.

- Sofia Fedorova as The Sailor’s Mother. Sister of Mikhail, Fedorovoa (1879-1963), danced with the Bolshoi Ballet, and was part of the Ballet Russes’ first Paris Season in 1909. On that opening night in 1909 she danced the Young Polovtsian Girl in the Polovtsian Dances (1909). She was diagnosed with a mental illness in 1913, and after retiring in 1928 she taught during her coherent phases, and was institutionalised when she wasn’t.

- George Balanchine as Snowball, a Blackman and A Beggar. Balanchine (1904-1983), like a lot of Ballet Russes dancers, came through the Imperial Ballet School. Before his defection he had assembled a Youth Ballet to showcase his choreography, and a younger generation of dancers. And like a lot of choreographers, he’d dance roles in his works, later appearing as Drosselmeyer in his version of The Nutcracker for the New York City Ballet.

- Constantin Tcherkas as The Dandy. Tcherkas (1908-1965) trained under Enrico Cecchetti and Bronislava Nijinska, and danced with the Ballet Russes from 1923-1929. He originated the part of The Nobleman in The God’s Go A-Begging (1928). He later worked at the Paris Opera Ballet as a Ballet Master and Choreographer.

- Monsieurs Jazvinsky and Winter as Journalists and Newsvendors.

- Monsieurs Hoyer and Cheplinsky as Policemen.

- Michel Pavlov as Cab Driver and King of the Ogres.

- Mezeslav Borovsky and Monsieur Petrakevich as Telescope Keepers.

- Monsieur Lissanevich as a Waiter.

- Monsieur Romov and Marjan Ladre as Street Hawkers.

- Monsieurs Hoyer II, Ignatov and Strechnev as Workmen and Newspaper Boys.

- Monsieurs Petrakevich and Marjan Ladre as Clowns.

- Richard Domansky as Officer.

- Albert Gaubier as Chimney Sweep.

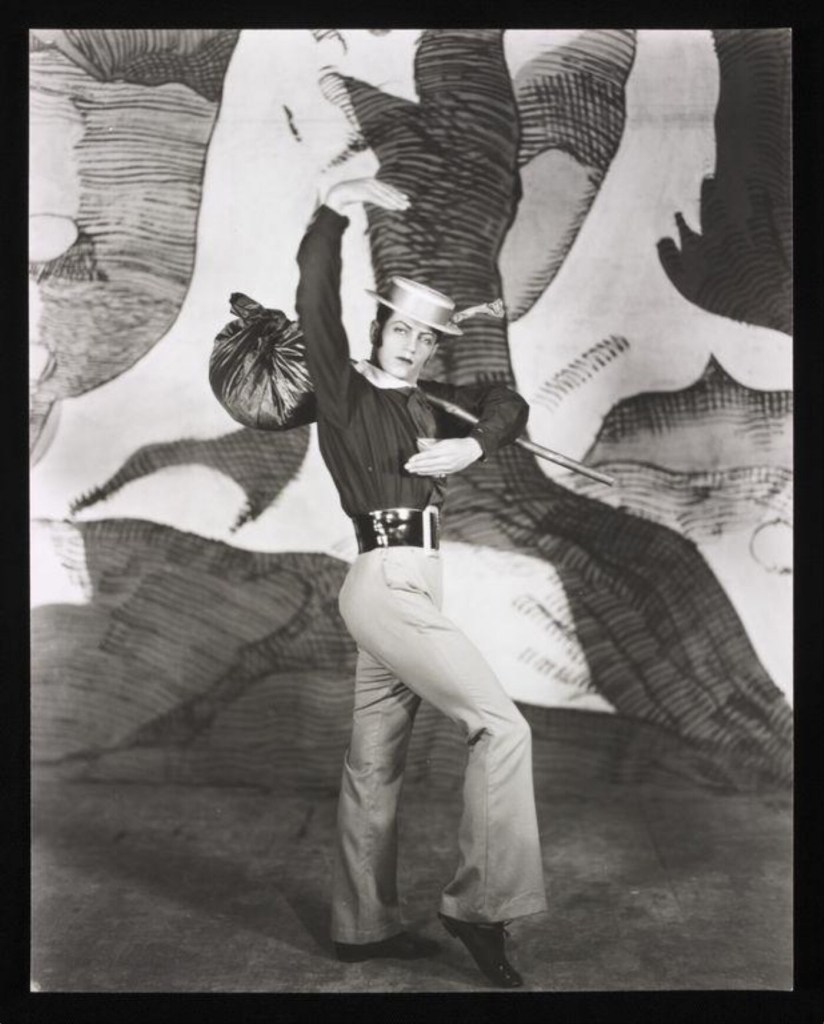

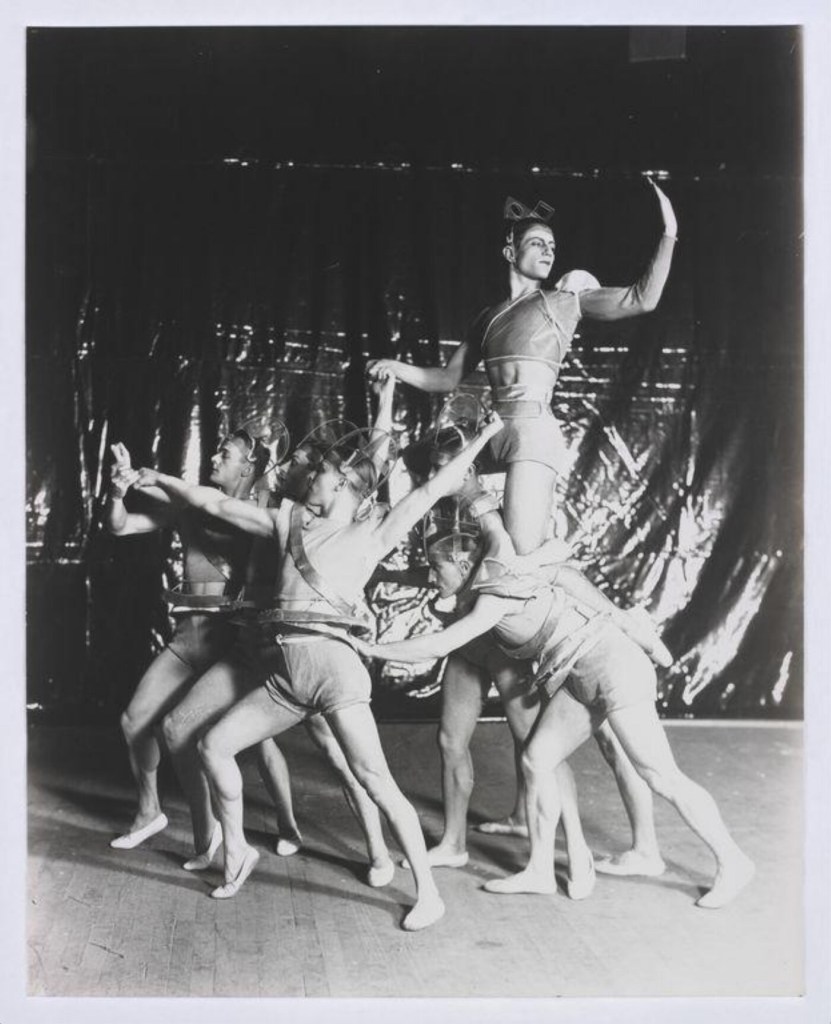

Beaumont doesn’t list Tamara Geva as Britannia and Stanislas Idzikowski as Cupid. However the V&A holds photos of both Geva and Idzikowski in costume.

Geva (1906-1997) was Balanchine’s first wife, who defected alongside him and Danilova in 1924. She left the Ballet Russes in 1927, having divorced Balanchine in 1926, and went to America, where she starred in films and performed on Broadway. She originated the role of Vera in On Your Toes (1936), which featured a ballet by Balanchine, Slaughter on Tenth Avenue.

Idsikowski (1894-1977) danced with Anna Pavlova’s company before joining the Ballet Russes. He originated the roles of The Snob in La Boutique Fantasque (1919) and Cloviello in Pulcinella (1920). He later danced with the Vic-Wells (now the Royal Ballet) in its early years, and would teach class there.

Geva’s role, Britannia, is actually that of the Goddess, played at the premiere by Lydia Sokolova. Geva writes in her memoirs, Split Seconds, that her and Sokolova resigned from the Ballet Russes around the same time, so it’s probable they rotated in the part between the premiere and the time they left the company.

The role of Cupid was added after the premiere; according to the George Balanchine Foundation this happened in early 1927. They also state that within 6 months of the premiere several of the minor roles had been omitted.

But, having putting this all together, we have our cast. Now we need the crew.

The Triumph of Neptune

The ballet itself was a pantomime ballet. This means the work contains extensive use of both ballet and mime. A famous example is Giselle, in which much of the plot in conveyed through mime. Triumph was split into 2 Acts, with six scenes in each Act.

Interestingly, the music for the ballet was written before the ballet itself had even been planned. The composer was Lord Berners (1883-1950), who would later compose music for three of Frederick Ashton’s ballets: A Wedding Bouquet (1937), Cupid and Psyche (1938), and Les Sirènes (1946).

According to Cyril W. Beaumont, it was Berners who approached Diaghilev about the music he had written being used for a ballet. Diaghilev agreed that it could work, and brought in Sacheverell Sitwell to write the scenario.

Originally Diaghilev wanted a ballet based on the Elizabethan Period, but in the end the ballet was based on the Toy Theatres of B. Pollard and H.J Webb, and fashioned like an English Pantomime. To do this they visited Benjamin Pollock’s Toyshop in Covent Garden, London, and it was from there that the ballet took shape.

Beaumont describes each of the 12 scenes that make up the ballet. I have summed them up in my own words.

Act 1, Scene 1: A London crowd gathers around a magic telescope, which allows viewers to see the fairy realm. A journalist, W.Brown, and Tom Tug, a sailor, are going to undertake a voyage to the fairy realm.

Act 1, Scene 2: In Cloudland, the Daughters of the Air are see frolicking amongst the clouds.

Act 1, Scene 3: W.Brown and Tom Tug set off, to crowds waving them farewell. Almost immediately, Tom Tug’s wife begins cheating on him with the Dandy.

Act 1, Scene 4: A storm interrupts the voyage, and W.Brown and Tom Tug end up clinging to a rock in the ocean, where they are saved by the Goddess.

Act 1, Scene 5: Two rival newspapers try to find out news of the explorers.

Act 1, Scene 6: In a fairy glade, at dusk, and in the middle of winter, fairies are seen enjoying themselves in the snow.

Act 2, Scene 1: The Dandy and the Sailor’s Wife dance a polka, being interrupted by the Spirit of the Sailor. The Spirit threatens them with a knife, but by the time the police arrive the Spirit has gone.

Act 2, Scene 2: In a grotto, W,Brown and Tom Tug are attacked by giants, but they fight their way towards the castle, where the King of the Ogres lives.

Act 2, Scene 3: The King of the Ogres saws W.Brown in half, killing him. Tom Tug, however, manages to escape.

Act 2, Scene 4: Snowball, while drunk, breaks the telescope, and all human communication with the fairy world is severed.

Act 2, Scene 5: Tom Tug returns home and is disgusted by his wife’s infidelity. He ends up becoming a Fairy Prince, and marrying the Fairy Queen, who is Neptune’s daughter.

Act 2, Scene 6: The Fairy Queen and Tom Tug are married.

The George Balanchine Trust says that within six months of the premiere, Act 1 Scene 5, Act 2 Scene 2 and Act 2 Scene 3 had been removed, and a variation for Cupid had been added. This must’ve streamlined the ballet a bit, taking out the least important parts to the overall plot.

Alexandra Danilova writes about The Triumph of Neptune in her memoirs, Choura. After Balanchine and Geva’s divorce Balanchine and Danilova began a relationship (though they never married), and Triumph was the first ballet Balanchine choreographed for her.

It was a subtle little ballet, rather Victorian in style–sort of nineteenth-century with some twentieth-century spice. For that reason it seemed very up-to-the-minute, not really old fashioned. The positions were classical, as in [Marius] Petipa, but the steps were speeded up, faster than they would have been if Petipa had choreographed them….So it was a little more interesting than traditional classical choreography.

Alexandra Danilova, Choura, Page 88

Beaumont writes that Act 1, Scene 2 (Cloudland) and Act 1, Scene 6 (The Frozen Fairy Wood) were particularly charming, and provided good dancing opportunities for Danilova, Petrova and Tchernicheva. There was also a hornpipe dance for Danilova and Lifar in the final scene, which was similarly charming. He states that the ogres weren’t that successful, which gives more of a reason to the scene involving them being taken out.

All in all, the ballet seems to have done its job. It wasn’t revolutionary like some of Balanchine’s later ballets, but it was charming, and successful enough to be revived. And, as we know, Balanchine went on to have a lot more successes.

So why is it forgotten?

Diaghilev believed that film couldn’t capture the essence of the Ballet Russes. While this was probably true, considering the technology available, it also meant that we don’t have much idea of anything when it comes to some of their ballets. And even some of the ones that are performed today, aren’t performed with their original choreography. Balanchine himself would make his own versions of The Firebird and Le baiser de la fée, both originally by the Ballet Russes.

Balanchine also revised and revived some of his earlier ballets later on in his career. This one didn’t make the cut. Considering it seems to be rather entrenched in the tropes of English pantomime, and made for a English audience, it’s perhaps not surprising. It was a novelty, and if it wasn’t one of Balanchine’s strongest he might’ve figured it wouldn’t sustain an audience, especially outside of England. Critics wouldn’t be endeared to something created for a ‘popular season’, so if you’ve got no critics, and no audience, who have you got?

I think it’s important to mention, at least from my perspective, the death of Diaghilev. The Ballet Russes would break down into various offshoots. Some of their dancers would go to these offshoots, some would go elsewhere, and some would retire. The only way they could revive previous ballets was if they had someone who remembered them. If nobody else remembered Triumph, and Balanchine didn’t care for it either, then we’ve ended up with no critics, no audience, no dancers and no choreographer. And so, it was forgotten.

In the last entry in this series (see here), the ballet was forgotten because it just wasn’t very good. However this one is different. I don’t believe that Balanchine could’ve made a terrible ballet, and from the words of Danilova and Beaumont, it seems, at least from a choreography standpoint, that it wasn’t terrible. While it would have aged rather interestingly, given the rise in neoclassical leotard ballets that Balanchine himself help popularise, perhaps The Triumph of Neptune deserved a longer shelf-life. Even if it was just a few more years than it had.

Sources

Beaumont, Cyril W. (1956). The Complete Book of Ballets. Putnam, London, England.

Danilova, Alexandra (1986). Choura. Alfred A. Knopf, New York, USA.

Geva, Tamara (1972). Split Seconds. Harper & Row, New York, USA.

Haskell, Arnold & Richardson P.J.S (2010 Reprint). Who’s Who in Dancing, 1932. Noverre Press, Hampshire, England.

Balanchine Foundation on The Triumph of Neptune: http://www.balanchine.org/display_result.jsp?num=64

Imperial Ballet School/Vaganova Academy Graduates (Russian): https://vaganovaacademy.ru/academy/history/vipuskniki.html

Benjamin Pollock’s Toyshop, Covent Garden: https://www.pollocks-coventgarden.co.uk/about-us/our-history/

Pollock’s Toy Museum, London: https://www.pollockstoymuseum.co.uk