Marie Taglioni is credited with being the first dancer to truly dance en pointe. Born in Stockholm, Sweden to dancer and choreographer Filippo Taglioni and Swedish dancer Sophie Karsten, it was under her Father that she rigorously trained. Today she’s most known for originating the title role in La Sylphide (1832), a ballet which utilised pointe work in a way that ballet hadn’t before, and changed ballet as a whole.

It was after her contract with the Paris Opera Ballet had expired that Marie travelled to Russia, alongside her Father. And the public in Saint Petersburg were very much overjoyed with her engagement there.

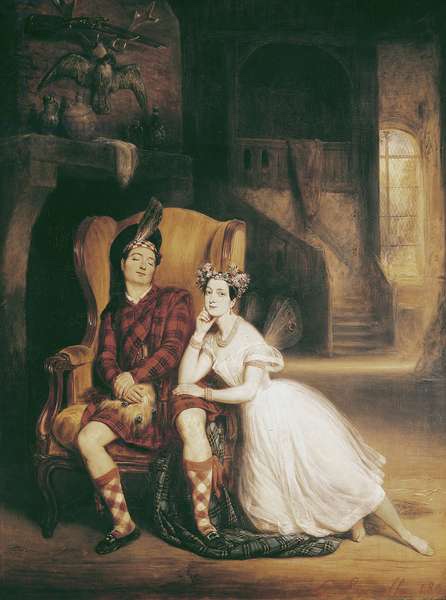

Taglioni

Marie was born on the 23rd April 1804. Her Father Filippo (1777-1871), as mentioned, was a dancer and choreographer. Her paternal Grandfather, Carlo (1754-1812) had also been a dancer and choreographed, working in various theatres around Italy. Filippo trained as a dancer in Paris and Italy, and ended up in Stockholm after accepting a job with the Royal Swedish Ballet.

Marie’s Mother Sophie Karsten (1783-1862) also came from a performing family. Her Father Christoffer Christian Karsten (1756-1827) and Mother Sophie Stebnowska (c.1753-1848) were both opera singers, and both were engaged at the Royal Swedish Opera. Sophie’s sister Elisabeth Charlotta Karsten (1789-1856) was a painter.

Combine that with Marie’s young brother Paul (1808-1883) also becoming a dancer and choreographer, and you have a rather accomplished family.

Filippo worked across Europe in the first two decades of the 19th Century, and Marie, her Mother and her brother mostly lived in Paris. Her first dance lessons were under her Father’s instructor, Jean-François Coulon (1764-1836). These first lessons, did not go well. Marie would stoop over a lot, causing the other students to call her a hunchback. But she seemed to attend class diligently.

In 1822 she was brought to Vienna, where Filippo was working. Upon seeing that he wasn’t as developed as a dancer as she thought, he spent 5 Months training her himself. She made her debut on the 10th June 1822, in a divertissement choreographed by her Father.

Filippo tried getting an engagement at the Paris Opera for himself and his children in 1824, but was disillusioned with the brusque treatment he received. It wouldn’t be until 1827 that they returned to the Opera, with Marie receiving 6 performances. At the time the regulations said 6 performances must be given by a dancer before any contract was signed.

Marie made her debut on the 22nd July 1827 in Le Sicilien. This ballet originally premiered three years before, and Marie’s solo pas was inserted into the ballet, as was customary at the time. And from there, everything changed.

Filippo became a choreographer for the Opera, and Marie and Paul became dancers. Marie would dance for the Opera more regularly than Paul, and remained fully attached to the Opera from 1827-1837. Among Filippo’s ballets were Le Dieu et la bayadère (1830) La Sylphide (1832) and La fille du Danube (1838). Marie originated roles in her Father’s ballets, as did Paul.

Taglioni’s contract with the Paris Opera expired in April 1387, and it was after this that her and Filippo travelled to Russia. From September 1837-February 1838 the pair were jointly paid 32,400 rubles. She was offered three benefit nights, and her Father two. The money made from these nights would go to the dancers, and an average benefit would bring in around 26,000 rubles. This was a highly favourable wage, and it’s not a surprise that Marie and Filippo accepted the offer.

Russian Ballet

In the 1830s, Russian ballet wasn’t as renowned as it would become. The Golden Age of Russian Ballet, associated with Marius Petipa, was yet to come, and we don’t know as much about the new ballets being presented. What we do know, is that a lot of the ballets were brought over from Western Europe.

Charles Le Picq (1745-1806) and Charles Louis Didelot (1867-1837) were among foreigners who were engaged as maîtres de ballet. Both men were dancers and choreographers also. It was under these pair that we are able to see the shaping of a permanent and renowned ballet company.

The majority of the Russian Tsars, or their Consorts, were involved with the arts. Performances would be held to commemorate coronations, to please visiting dignitaries, and celebrate military victories. The Imperial Ballet and the Monarchy would remain intertwined until the revolutions of 1917.

Ballet at the time was held on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays. The typical season would run from just after Easter, to the second day of Lent. Marie wouldn’t stay in Russia for the whole of the season, and would dance abroad, particularly during the Summer months.

Her Arrival

There was a lot of hype that built around the Taglioni’s visit. Some of the Saint Petersburg elite, who could afford to travel, had seen her dance in Paris, and more had letters written by friends who had.

Her Russian debut was on the 6th September 1837 in La Sylphide, performed at the Bolshoi Theatre in Saint Petersburg. This theatre is not to be confused with the most famous Bolshoi Theatre (home of the Bolshoi Ballet), which is in Moscow. Saint Petersburg’s Bolshoi Theatre was the home of the Imperial Ballet before they moved to Mariinsky Theatre in 1886.

Marie Taglioni was recalled at the end of the first act, after her dance in the second act, and three times at the end of the ballet.

Severnaya Pchela (Northern Bee) Newspaper, 7th September 1837

La Sylphide was undoubtably both Marie and Filippo’s greatest triumph. The use of pointe work as an aesthetic shaped the Romantic Ballet, and Taglioni was affectionally dubbed ‘Our Sylphide’ by the Parisian public. Outside of her French and Russian performance, she’d also perform the role in London (in 1832) and Milan (1841).

The Reactions of the Public

Ivor Guest writes that tickets for that first performance were essentially like gold dust. To not be there for the debut of the great Marie, why you could never show your face in society again! Tickets to all of her performances became sought after, and people would queue outside the theatre each morning to try and get them.

It’s also said that at one of Marie’s early performances, the Emperor (at the time Nicholas I) moved down from the Imperial Box into the stalls to get a better view of the stage. A statue of Marie was put in the Imperial Box, and it wasn’t uncommon to see Nicholas in attendance when Marie was dancing.

Taglioni fell ill in late 1838, not returning to the stage until January 1839. This quote from the Severnaya Pchela sums up the public reaction.

Taglioni has been ill for two whole weeks, and all this time Petersburg has been suffering from spleen. Other artistes try to divert the public, but all in vain.

Severnaya Pchela, 9th December 1838

Overall, Taglioni was adored by the public. Her artistry and grace were admired, and, as Russian ballet education wasn’t as advanced at the time, the homegrown dancers paled in comparison.

Plus, with the Taglionis came the ballets, many of which, had never been performed in Russia before.

The Ballets She Performed

The Taglioni’s contract was renewed 4 times. Over those years Marie danced approximately 200 times (and obviously wasn’t dancing when she was ill). Over that time she performed in a range of ballets, including:

- La Sylphide

- La Gitane, which premiered on the 23rd November 1838, shortly before Marie became ill. This was a completely new ballet, choreographed by Filippo. Marie danced the role of Lauretta, opposite Nicholas Osipovich Goltz as Ivan. The ballet followed Lauretta, who was kidnapped by ‘gypsies’ as a child. It was performed in London at Her Majesty’s Theatre in June 1839, during the Russian off-season, with Taglioni in the lead role.

- L’ombre, another new Filippo ballet. She first danced this role on the 28th November 1939. L’ombre, or The Shadow, was about a murdered girl (Marie) who haunts her former lover to prevent him from marrying another. Review note there was a good pas de trois for Marie, Goltz and Mme. Apollonskaya, suggesting they might”=3 danced the roles of the former lover and his new beau respectively. This ballet was also produced in London, but in 1840.

- La Fille du Danube. Marie mainly appeared in ballets choreographed by her Father, and this was another. This one however, had premiered in Paris in 1836. Marie originated the role of Fleur-des-Champs. She reprised the role in Russia, with the ballet first being presented in 1837.

- La Bayadère Amoureuse. This Filippo ballet seems to also be known as Le Dieu et la Bayadere. It was an opera-ballet based on Goethe’s ballad Der Gott und die Bajadere, that premiered in Paris in 1830. Marie danced the role of Zoloe.

- Le Corsaire. There is a popular ballet by this name, but that premiered in 1856. An earlier ballet adaptation of Byron’s Corsair poem did premiere in London in 1837, though this was choreographed by Albert (1789-1865) and did not feature Marie in the premiere cast. It’s possible that if this was the production the Taglioni’s brought with them the choreography was tweaked by Filippo.

- Aglaë, ou L’Elève de l’amour. This was a short divertissement by Filippo in which Marie danced the role of Aglaë. It was produced in London in 1841.

- Gerta. Marie danced opposite Christian Johannson in this ballet. Johannson (1817-1903) would become an accomplished teacher after retiring from dance, teaching students like Pavel Gerdt, Platon Karsavin and his daughter Tamara, the Legat brothers (Nikolai and Sergei), Agrippina Vaganova and Anna Pavlova,

- Le lac des fées. This seems to be a ballet known by the name Озеро волшебниц (Lake of the Enchantress) in Russian. It was another Taglioni ballet, probably premiered in 1841, and featured Olga Schlefocht along Marie.

- Dya

The Taglioni’s stayed in Saint Petersburg, but there were continued efforts to get them to Moscow as well. These negotiations seem to have broken down like most do- the money problem. The Taglioni’s were reported to have wanted 3,000 rubles per performance and a benefit for Marie. However these terms would not be met, and Marie would never dance in Moscow, which, at the time, was the ‘old capital’ of the Russian Empire.

Departure & Influence

Marie had a few ‘final performances’ in Russia. Her last benefit was on the 26th January 1842, when she appeared in Yetta, Reine des Elfrides. She’d dance a ‘final final performance’ on the 1st March 1842, being recalled before the curtain 18 times. Then, as the public still didn’t want to part way with Marie, she appeared in two more performances during Lent.

Eternally, you will be engraved in my heart, and if I say goodbye to Russia, it’s not for forever.

Translation of Marie’s Curtain Speech, 1842

Despite this speech, Marie and Filippo never returned to Russia. It appears the speech was more of a diplomatic promise from Marie. After 1842 she danced in London, and returned to the Paris Opera in the Summer of 1844, to give a set of farewell performances. She’s retire three years later, but would assist in teaching and guiding the Paris Opera, as well as doing freelance teaching of her own.

Her departure would also lead to one of the most enduring stories in dance history. The belongings of her house in Russia were auctioned off in March 1844, and it’s said that a pair of her shoes was sold for 200 rubles. The balletomanes who brought the shoes apparently cooked them, served them with a sauce, and ate them. Whether this is true or not I couldn’t say, but the fact that people rushed to buy her things shows how adored she was.

The downside of this, is that it left a bit of a hole in the Imperial Ballet. No Russian ballerinas were internationally renowned at this point, and a lot of ballets were ridings on great ballerinas to lift the work up. The ballerinas of the company had learnt and studied with Marie, but the audience were rather reluctant to watch anyone else in ‘Marie’s parts’. It came down to three performers to inherit those parts:

- Olga Timofeyevna Schlefocht (1822-1845) studied at the Imperial Theatre School, but blossomed when she studied alongside Taglioni, gaining leading roles at the age of 17 in 1839. She graduated from the school in 1841, but unfortunately would pass away from consumption four years later.

- Tatiana Petrovna Smirnova (1821-1871) inherited a lot of Marie’s parts, and was preferred by the public as the successor. She’d be granted a benefit performance just two years after leaving the Imperial School, an unprecedented honour. She’d retired in 1854.

- Elena Ivanova Andreyanova (1819-1857) is the most well-known of the three today. She was initially scorned by the public in Taglioni’s roles, but became the first Russian to dance the title role in Giselle in 1842, which established her as one of the first true Russian ballerinas. She’d gain permission to go abroad without being fired, and danced in Paris and Milan, but her tours abroad would leave her in ill health, and she passed away in 1857.

Marie’s successor as prima ballerina of the Paris Opera Fanny Elssler would appear in Russia in 1848, being just as successful as Marie. Foreign dancers would continue to appear in Russia, as would choreographers Arthur Saint-Léon and Marius Petipa. But, the rise of the Russian ballerina would appear at the turn of the 20th Century, with Mathilde Kschessinskaya, Anna Pavlova, Tamara Karsavina and Olga Preobrajenska leading the way.

Marie would be fondly remembered in Russia. N. Soloviev wrote a book on Marie, published on Saint Petersburg in 1912, and the great Russian dance critic Valerian Svetlov (1860-1932) apparently kept a pointe shoe of Marie’s in his personal collection.

Overall, I’d say Marie and Filippo’s visit was monumental in Russian Ballet. They were able to introduce new ballets, new aesthetics, and the visit helped lift up the native ballerinas, even if they were unfairly compared to Marie at first. The continuing visits of Westerners to the Imperial Theatre would end, of course, in the Golden Age of Russian Ballet.

Sources

Beaumont, Cyril W. (1956). The Complete Book of Ballets. Putnam, London, England.

Beaumont, Cyril W. (2020 reprint). A History of Ballet in Russia. Noverre Press, Hampshire, England.

Guest, Ivor (1966). The Romantic Ballet in Paris. Pitman and Sons, London, England.

Olga Timofeyevna Schlefocht (Russian): https://ru.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Шлефохт,ОльгаТимофеевна

Marie’s 1842 Curtain Speech in French: Eternellement, vous serez gravés dans mon cœur, et si je fais mes adieux à la Russie, ce n’est pas pour toujours.