The late 19th-early 20th century was the Golden Age of Russian Ballet, with the Imperial Ballet being at the centre of it. And, for the first time, the Russian Ballerina was equal. Mathilde Kschessinskaya had become the first Russian Ballerina to master the 32 fouettes, originally done by Italian Pierina Legnani, and we’d soon see talents like Anna Pavlova rising through the ranks. But there are also some lesser known ballerinas, one of whom was an unlikely one.

In Spotlight On, I aim to focus on individuals, or theatrical shows, that have contributed a lot to the art as a form. For individuals, I aim to provide a glimpse into their life and works, and make people more familiar with them.

Note: Not all of my sources state whether the dates given are on the Old Style [O.S] or New Style [N.S] Calendar (i.e. the Julian and Gregorian calendars respectively). The Gregorian calendar came into use in Soviet Russia on the 31st January 1918, the day after being the 14th February 1918. I have tried to work around this as much as I can.

Birth and Early Life

Olga Iosifovna was born on the 2nd February [N.S] 1871, in Saint Petersburg. While her surname was Preobrazhenskaya, she’d use Preobrajenska professionally, and most sources pick one or the other to stick to.

Olga didn’t come from a performing family. This wasn’t uncommon — contemporaries Anna Pavlova and Lyubov Yegorova had this in common with Olga — but it does mean we know less about her background. What we do know, however, is that her parents were determined.

At the age of 7 Olga was sent to her ballet lessons under Leopoldina Lozenskaya. Lozenskaya graduated from the Imperial Ballet School in 1875, joining the Mariinsky, and was still in the company in 1881, but I can’t find much more on her than that.

The determination comes into play because Olga wasn’t accepted into the Imperial Ballet School upon her first audition. She was described as short and puny, with dancer and future teacher Christian Johansson (1817-1903) calling her a ‘hunchbacked devil’. It took her three tries to be accepted, finally entering the Imperial School in 1879 at the age of 8. To match up the timeline, this would mean she was sent to Lozenskaya after her second failed audition.

Schooling

The [evening] performance over, she went to take her lesson with the Maestro [Enrico Cecchetti]; it lasted far into the night. Artists respected her greatly for her perseverance and loved her gentle ways. Her ultimate success was greeted with enthusiasm by all.

Tamara Karsavina on Olga’s continued learning, Theatre Street, P119

Russian ballet instructors are often aware whether they’re training a future prima ballerina. And yet Olga seems to have surprised them. She was musical, but her posture and frailty set her back, and she wouldn’t have stood out to her teachers if it weren’t for her determination.

At school she was taught by a variety of teachers, including the Imperial School’s finest. Yekaterina Vazem (1848-1937) was one of the most well-known female teachers at the school, having originated the role of Nikiya in La Bayadère (1877). Johansson, Lev Ivanov (1834-1901) and Pavel Gerdt (1844-1917) made up the intermediate and advanced instructors. All three were top dancers and teachers, and in Ivanov’s case, a choreographer.

It is said that during her youth Olga wore a steel corset for the whole of a Winter, to help right her back, and she put a lot of work into strengthening her technique, along with her muscles. This determination and perseverance would continue into her company years, with Fyodor Lopukhov (1886-1973) writing that she ‘showed a rare exactingness towards herself’ while in class. Lopukhov considered her one of the top ballerinas of her time, alongside Yekaterina Geltzer (1876-1962) and Lyubov Roslavleva (1874-1904), both of the Bolshoi.

Olga’s graduation performance was in March 1889. The graduating class wasn’t full of stars, but there were a few well-known graduates, like:

- Alexey Bulgakov, who would dance Von Rothbart in the 1895 production of Swan Lake.

- Alexander Gorsky, a choreographer and ballet master, who would re-stage Marius Petipa’s ballets in Moscow and Saint Petersburg. His productions of ballets like Don Quixote have become the blueprint, with modern versions deriving from his stagings.

- Anatoly Panteleev, who would dance the Venetian, or Neapolitan, Dance in the 1895 production of Swan Lake.

At her graduation performance, Olga would feature in two dances. The character pas de deux from Act 2 of La Esmeralda. La Esmeralda had premiered in London in 1844, with music by Cesare Pugni and choreography by Jules Perrot. Perrot himself would stage the production for the Imperial Ballet in 1849. Marius Petipa then restaged the ballet in 1886.

The other piece she danced was the pas de trois from The Pearl of Seville. Marius Petipa created The Pearl of Seville in 1845, while he was working at the Teatro Real in Madrid, Spain. A later ballet of the same name was created by Arthur Saint-Léon in 1861 for the Imperial Ballet. Neither is extant today.

Olga graduated into the corps de ballet, and for her first two years in the company, that was where she remained.

An Unlikely Ballerina

Small in stature, with bubbly calf muscles, homely in real life and charming on stage, Olga Preobrazhenskaya tempted us with her rare industriousness and insistent striving for the expressiveness of each movement, in what is called the imagery of dance.

Fyodor Lopukhov on Olga, Sixty Years in Ballet, P108 (translation from Russian my own)

It is hard to know just how much accounts of the time suffer from bias, particularly when it comes to the ranking and importance of the dancers. Multiple sources, however, state that Olga’s initial rise as a ballerina was hindered by someone who was holding onto a repertory that would suit Olga.

Mathilde Kschessinskaya (1872-1971) was one of the undoubted prima ballerinas of the Imperial Ballet, being the first Russian dancer to master the 32 fouettes (famously part of the Black Swan pas de deux in Swan Lake). However her own achievements always have a cloud cast over them, and that cloud is her love life. She was involved with the future Tsar Nicholas II before his marriage, and then had affairs with both Grand Duke Sergei Mikhailovich and Grand Duke Andrei Vladimirovich. It’s said her influence at court meant she could hold onto roles she coveted, and a legendary incident involving chickens would show her jealously.

But we’ll talk about the chickens later. For now, Olga was stuck in the last row of the corps, the least senior rank of the company. At the time she had no patrons, and no attention from critics. It wasn’t until 1891 that she received attention. But not for being cast. Instead, it was for covering injured or ill soloist roles.

That year she danced the Pas Chinois in Catarina, ou la fille du bandit. This Jules Perrot ballet had originally premiered in 1846, and was first staged in Russia in 1849. Petipa had revived the ballet in his own production in 1870. In this role she was praised by critic Alexander Pleshcheyev. The same year Olga substituted for Mathilde Kschessinskaya as the Fairy Candide in Petipa’s Sleeping Beauty.

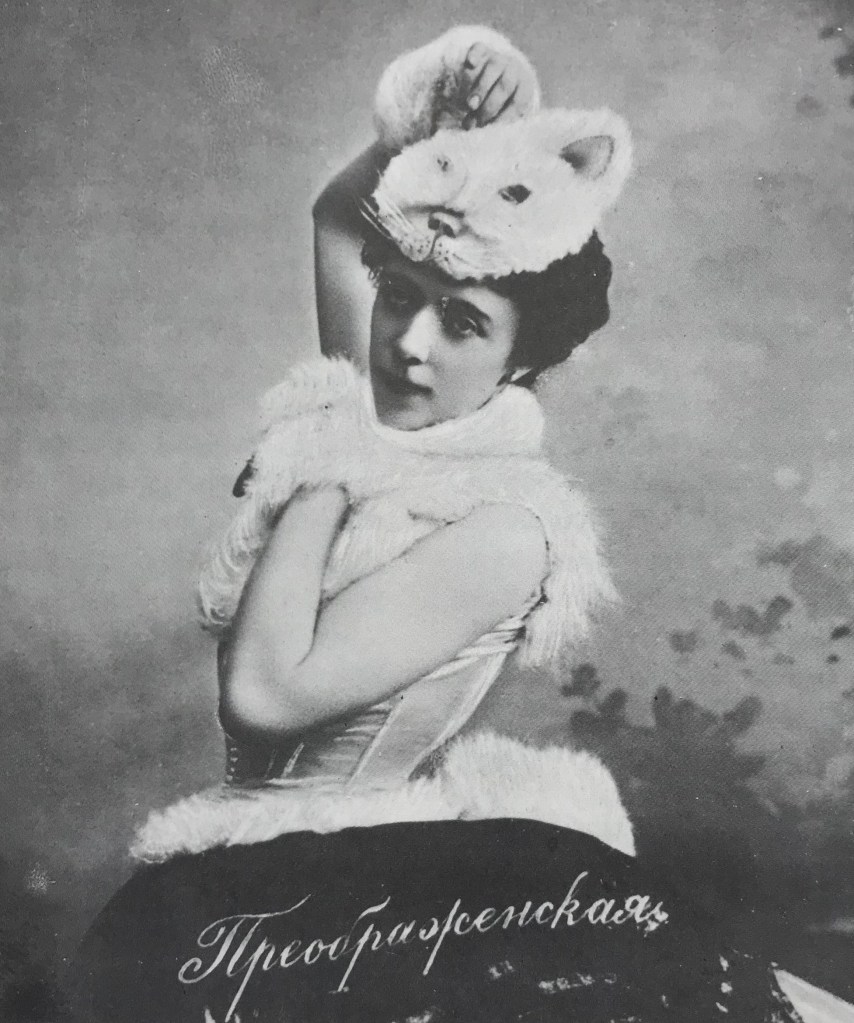

In 1893 she’d once again dance a larger part in Sleeping Beauty, going on as the White Cat. Throughout the next few seasons, she’d dance in Operas like Carmen, ballets like Paquita, and as Columbine in The Nutcracker.

In February 1895 Olga made her first appearance abroad, joining a small group led by Kschessinskaya. Alongside the pair was Mathilde’s brother Joseph, Alfred Befeki, and Georgy Kyasht, brother of Lydia Kyasht. They danced at the Casino Theatre in Monte-Carlo, and this would be the first of many appearances abroad for Olga.

Just before the tour to Monte Carlo Petipa and Lev Ivanov revived a failed ballet from 1877, which had a score that was described as ‘too noisy’, and original choreography by a man named Julius Reisinger. You may not know his name, and that’s because Petipa and Ivanov’s revival of Swan Lake has eclipsed the 1877 production.

Olga danced the pas de trois in the 1895 revival, alongside Georgy Kyasht and Varvara Rykhliakova. The following year she’d dance Anne in the premiere of Petipa’s Bluebeard, and would originate the role of Henriette in 1898’s Raymonda.

1898 was a turning point for Olga, as more roles were added to her repertory. One of her most outstanding achievements was the title role in Petipa’s Whims of the Butterfly. She danced the role of the Fly in the 1895 revival, but would become arguably the most celebrated performer in the Butterfly role, with Fyodor Lopukhov considering it one of her most celebrated roles.

The same year she’d gain the roles of Swanhilda in Coppelia, Galatea in Acis and Galatea, and Terese in Halte de Cavaliere. These are all ballets which can be classed as comedic, and comedy was where Olga shone.

Her role was close to lyric-comedy, which did not prevent her from dancing dramatic parts with dignity, like Raymonda and Anne.

Her elevation and ballon were small; her terre-a-terre movements were especially successful. Her role should have been called comic-ingénue. But Olga’s talent did not fit into this definition.

Fyodor Lopukhov, Sixty Years in Ballet, P108 (translation from Russian my own)

Four years after the premiere of Bluebeard, Olga would debut in the leading role of Ysaure. Gennady Smakov wrote that she started that performance, on the 3rd September 1900, a soloist, and ended it a ballerina.

From this point onwards, Olga would get a shot at the classics. Her Giselle and Odette/Odile were not considered successes (though Petipa, always conscious of his style being retained, admired her Swan Lake), but her Aurora was more celebrated.

Sylvia was produced in the 1901-1902 season, a new production, done primarily by Lev Ivanov (until his death in December 1901), and then Pavel Gerdt. Olga would dance the title role, opposite Sergei Legat as Aminta. This was not a success, and would only end up having 5 performances, but another Gerdt production of an existing ballet, Javotte, would be more successful, and would become one of Olga’s celebrated roles.

But her most celebrated role would be Raymonda, and it’s through this role that we can get an idea of what Olga’s dancing must’ve been like. It was common at the time to change steps of variations to match the strengths of the dancers, and Olga’s Raymonda has been notated. The Sergeyev Collection is a series of dance notations, using the method of Vladimir Stepanov. The collection is named for Nicholas Sergeyev, who brought the collection out of Russia after the revolution, and used it to stage ballets. Raymonda was notated in 1903, with Olga in the title role.

It’s interesting to note that what we like best in the third act of Raymonda we owe to Olga Preobrazhenskaya- a series of classical dance movements into which Hungarian folk dance has been introduced (for Legnani, Petipa had other choreography).

Fyodor Lopukhov on Raymonda, Sixty Years in Ballet, P109 (translation from Russian my own)

The critics were treating Olga like a Queen at this point. They admired her ability to show the technicality of every role she danced, even if her emotion wasn’t always there. But her determination had paid off, and as she continued to practise even when she was a prima ballerina, she became known as the most dedicated ballerina, a title she accepted. The other thing they admired was how her presence could lift a ballet, as 1902’s La Source would demonstrate.

La Source premiered in 1866 at the Paris Opera, with choreography by Arthur Saint-Léon. It was staged in Russia by the Italian ballet master Cesare Coppini, with Olga in the leading role of Naïla. It was not an overly successful ballet, and wasn’t popular with the dancers, who thought the plot was incomprehensible.

After several months of intense rehearsal, the production was ready- tawdry, stilted, impotent. The marvellous dancing of Preobrazhenskaya alone accounted for the ballet remaining in the repertoire. Even her superlative artistry could not redeem the absurdity of the plot nor save it from ridicule.

Tamara Karsavina, Theatre Street, P100

1906 brought about the revival of La fille mal gardée. Petipa and Ivanov originally staged the ballet for Virginia Zucchi in 1885, but Kschessinskaya had become the prime interpreter of the main female role, Lise. In 1906, Olga debuted in the role. And so, it’s time for the chicken story.

Frederick Ashton’s production of ballet, the version most known in the West, has a ‘chicken dance’, done by dancers in costume, but the Russian production utilised real chickens, in pens, of course. But they wouldn’t stay in the pens. Col. Vladimir Teliakovsky, Director of the Imperial Theatres and Petipa’s ‘nemesis’, recounts the incident, as quoted by Gennady Smakov:

Kschessinskaya took this assignment of the role as a personal insult and spared no possible means for causing trouble at the debut of her rival. It happened that the little door of the chicken cage was left open, and so during one of Preobrazhenskaya’s dances the chickens flew out over the stage, thus causing a certain commotion. But the truth is that nothing could upset Preobrazhenskaya; with imperturbable precision she performed her dance right to the end.

V. Teliakovsky, quoted in Gennady Smakov’s The Great Russian Dancers, P66

This story illustrates both the legendary jealously of Kschessinskaya, and the legendary determination of Olga. The pair must’ve been on somewhat amicable terms though, as they, alongside Nikolai Legat, guested at the Paris Opera in 1909. This visit, coming right at the start of the legendary Ballet Russes, was overshadowed, but during it, Olga performed the title role in Javotte, and Nikolai became the first male dancer in the Opera’s history to dance Franz in Coppelia, opposite Kschessinskaya as Swanhilda.

The death of Marius Petipa in 1910 closed the doors on the Golden Age of Russian Ballet. There were still new ballets, but not as many of them are extant, and, for the first time, the Russian dancers were venturing out. They brought with them ballets that had never been seen in the west before. And Olga, in 1910, brought England its first Swan Lake.

Odette/Odile wasn’t one of Olga’s most revered roles, but she was still more than technically competent in everything she danced. She danced the role at the Hippodrome, in London, bringing along with her a pick-up group of Russian dancers. The ballet had been cut down, into two acts (a full-length version would arrive with the Ballet Russes the following year), and premiered on the 16th May 1910.

Olga would also danced in South America, Dresden and Milan, mirroring the other prima ballerinas like Pavlova, Kschessinskaya and Karsavina, who embraced performing in new countries.

Not many new roles came to the Mariinsky in the 1910s. Nikolai Legat revived Petipa’s The Talisman in 1909, not long before Petipa’s death. Olga would dance the role of Niriti, along with Kschessinskaya and Karsavina. This role would be the one she danced at her farewell benefit performance in 1920, just over 30 years after joining the company.

The Revolution

There were three important revolutions that would shape the Imperial Ballet. The 1905 Revolution, and the February and October Revolutions, both of 1917. After the latter two they weren’t really an Imperial Ballet at all- Russia was now a republic. But due to the whole Imperial Ballet thing, it’s not hard to imagine how much it must’ve shaken the ranks.

Olga, on the other hand, was more cautious. But, as Karsavina writes, Olga’s benefit performance showed the sentiment and fear of the public at the time. The performance was on the 9th January 1905, and Olga was performing in The Whims of the Butterfly.

Towards the last act, alarming rumours ran in the theatre—riots had broken out in the town; the mob were on their way to the theatre; they had already broken into the Alexandrinsky and stopped the performance. Panic spread. The theatre quickly emptied. On stage the performance never so much as flickered.

Olga’s Benefit Performance, Theatre Street, P119

Lopukhov recounts that the day after this benefit Olga went to management, and officially requested permission to hold special benefit performances. The funds raised from these performances would go to the families of deceased workers. Her request was denied.

After the 1917 revolutions, Karsavina and Kschessinskaya had left Russia, but Olga stayed for a few more years. During those years she performed, and even as she grew old she continued to practise and develop her technique.

Olga Preobrazhenskaya was a selfless, artistically enthusiastic person; few of us in the early years after October [the Revolution] performed so much, with such devotion, at various venues, and met with the unfailing approval of the new audience of workers, peasants and soldiers.

Fyodor Lopukhov, Sixty Years in Ballet, P109 (translation from Russian my own)

Olga would leave Russia in 1921 via Finland, where she was performing. It is said she left due to a love she couldn’t bear to separate from. She reached Milan, and taught for some time at the Ballet School of La Scala. In 1923 she joined the large community of Russian émigrés in Paris, where she’d live for the rest of her life.

Teaching

The palm of supremacy in grace belonged to her. To infinite charm she added an unusual clear-headed judgement. She always knew the wherefore of perfection. She was very witty, and an excellent mimic. ‘Now, young beauty’, she would say. ‘Step off! Fire away! Control your arms if you don’t want a partner minus a few teeth’.

Tamara Karsavina on Olga, Theatre Street, P87

Olga started teaching around 1914 at the Imperial Ballet School. After emigrating, her Parisian studio in the Salle Wacker existed from 1923-1960. Both in Russia and outside of it she taught students who would become stars, and students who would become exemplary teachers. Some were at the start of their careers; others were established names when they came to Olga. A lot of students would go between Russian teachers, to become versatile all-rounders. Among the students Olga taught were:

- Alberto Alonso (1917-2007), who became a co-founder of the National Ballet of Cuba. He was also a choreographer, with his most well known ballet being Carmen Suite (1967).

- Irina Baronova (1919-2008), one of the three ‘Baby Ballerinas’ of the Ballet-Russes de Monte-Carlo. Irina studied with Olga after arriving in Paris in the late 1920s. Baronova wrote that Olga focused on making them both dancers and performers. She also wrote that Olga would sometime perform for the Russian emigrés in Paris, often bringing them to tears. Olga recommended Baronova to both George Balanchine and Serge Lifar, and Baronova wrote that after her first Odile, her thoughts were with Olga and her kindness as a teacher.

…her face suddenly lit up with a kind and mischievous smile and she stroked my hair. This kind gesture and her beautiful smile went straight to my heart. From that moment, I adored her. And I adored her through all the years to come, as she screamed at me, encouraged me, taught me. Whether she was demanding, irritable, cross or kind, I adored her, and will adore her memory to the day I die. She has my eternal gratitude.

Irina Baronova, Irina: Ballet, Love and Life, P58

- Ludmila Cherina (1924-2004), who danced with companies in France and Monaco and acted in films.

- André Eglevsky (1917-1977), who danced with multiple companies in Europe and the USA, and appeared in the Charlie Chaplin film Limelight (1952).

- Margot Fonteyn (1919-1991), who went on to become the Prima Ballerina Assoluta of the Royal Ballet. She, like a lot of students, studied with Olga, Kschessinskaya and Lyubov Egorova, all of whom had studios in Paris. She writes in her autobiography that ‘Preo’ was her favourite of the three.

Her daily class followed a very set pattern, to which one quickly became accustomed, though the pianist, another little émigré old lady, never could get it quite right. ‘Pourquoi poum-poum-poum?’ complained Preobrazhenskaya towards the piano. ‘Je veux poum-poum-poum-po-poum! No poum-poum-poum!’ And she would turn back to glower at the class until someone danced especially well, when she would rediscover her smile…..She taught all day, with a short lunch break, during which she had a morsel to eat before climbing on to a chair to put the crumbs out on a high windowsill for the birds, whom she loved much more than humans.

Margot Fonteyn on Olga’s Class, Autobiography, P65-66

- Maina Gielgud (born 1945), who danced with many companies across Europe and has been a noted teacher.

- Serge Golovine (1924-1998), a star of the Grand Ballet du Marquis de Cuevas during the 1950s.

- Irina Grjebina (1909-1994), who took lessons with Olga alongside her sister Lya. She danced at the Russian Opera in Paris before founding her own company.

- Alexandre Kalioujny (1923-1986), an étoile at the Paris Opera Ballet and a teacher in Nice, France.

- Natalya Lesli-Krasovskaya (1918-2005), who danced with the Ballet Russes de Monte-Carlo and the London Festival Ballet.

- Yvonne Mounsey (1919-2012), who became a dancer with the New York City Ballet, and later a teacher.

- Nadia Nerina (1927-2008), who studied with Olga in the Summer of 1947. She became a Principal Dancer of the Royal Ballet, originating the role of Lise in Frederick Ashton’s version of La fille mal gardée.

- Tamara Toumanova (1919-1996), another of the Baby Ballerinas, along with Baronova and Tatiana Riabouchinska. When they were both around 10, Toumanova and Baronova danced next to each other, in the front row of Olga’s classes (the front row was reserved for the best students).

- Nina Vershinina (1909-1995), who worked with the Ballet Russes de Monte Carlo, and the companies of Ida Rubenstein and Bronislava Nijinska. She later taught in Brazil.

- Olga Vershinina (later Olga Morozova de Basil, 1914-1993), a dancer with the Ballet Russes successor companies, and the third wife of impresario Wassily de Basil (1888-1951).

- Vera Zorina (1917-2003), who danced in the Ballet Russes de Monte Carlo and appeared in films, often choreographed by her then-husband George Balanchine.

- Nina Vyroubova (1921-2007), who became an étoile at the Paris Opera Ballet.

- Igor Youskevitch (1912-1994), who gained fame as an early star of the American Ballet Theatre, forming a brilliant partnership with Alicia Alonso.

- George Zoritch (1917-2009). Zoritch secured his first job after only 9 months of lessons with Olga. He danced with both the Ballet Russes de Monte-Carlo and the Ballet Russes of W. de Basil. He was a favourite of choreographer Léonide Massine, and also appeared in films.

Last Years

The story goes that, having lived to a ripe old age, she was in Paris, frail, sick, with no means of income, forgotten.

Fyodor Lopukhov, Sixty Years in Ballet, P109 (translation from Russian my own)

Unfortunately, time was not kind to the former prima ballerinas of the Imperial Ballet. Ballet dancing has never been a lucrative career, and the teachers like Olga who often waved away the issue of payment, they were left practically destitute. Kschessinskaya lived in her villa, but with an unkempt garden, and dust all over the tables. Egorova spent her last years dependent on aid from friends and ex-pupils. And Margot Fonteyn describes Olga’s last years better than I ever could.

Olga Preobrazhenskaya lived on in Paris to the age of ninety-four. To support herself she taught until her very last years, when her wandering mind repeated and confused the exercises. She died in a home with none of her beloved birds to console her but still so physically strong that she stacked the bedroom furniture against her door to prevent strange nurses from invading her loneliness.

Margot Fonteyn, Autobiography, P263

Olga passed away on the 27th December 1962 aged 91 (not 94). She is buried in Cimetière de Sainte Genevieve des Bois, Île-de-France, France.

Lopukhov laments the fact that Olga left Russia, stating that if she remained in the country she could’ve become a matriarch figure in Soviet Ballet. He also points out that she could’ve gained pensions. It’s impossible to know how true this hypothetical scenario would be, but it is definite that any student would’ve been lucky to work with Olga. By every account her teaching was superb, her dancing and technique were strong, and her kindness was appreciated by all.

She was a ballet master, as they used to say in the olden days, by the grace of God.

Fyodor Lopukhov, Sixty Years in Ballet, P109 (translation from Russian my own)

Sources

English

Baronova, Irina (2005). Irina: Ballet, Life and Love. Penguin/Viking, Melbourne, Australia.

Beaumont, Cyril W. (2020 reprint, originally 1930). A History of Ballet in Russia. Noverre Press, Hampshire, England.

Fonteyn, Margot (1976). Autobiography. Alfred A. Knopf, New York, USA.

Guest, Ivor (2006). The Paris Opera Ballet. Dance Books, Alton, Hampshire, England

Karsavina, Tamara (1950). Theatre Street. Readers Union, London, England.

Smakov, Gennady (1984). The Great Russian Dancers. Alfred A. Knopf, New York, USA.

Petipa Society Website: https://petipasociety.com

Russian

Lopukhov, Fyodor (1966) (Russian). Sixty Years in Ballet. Искусство (Art), Moscow, USSR.

Imperial Ballet School Graduates: https://vaganovaacademy.ru/academy/history/vipuskniki.html

Russian Webpage about Olga: https://www.belcanto.ru/preobrajenska.html

Great Russian Encyclopaedia Page about Olga: https://bigenc.ru/theatre_and_cinema/text/3175931

Paper on Olga’s Teaching by M. A. Vedernikova, 2011: http://vestnik.yspu.org/releases/2011_1g/57.pdf

Russian Culture Page about Olga: http://www.russianculture.ru/formb.asp?ID=79&full