The Ballet Russes became a sensation in the 1910s. Their first Paris season of 1909 led to further seasons in the city, along with engagements in London, Monte Carlo, and further beyond. Under the leadership of Serge Diaghilev top artists came together to produce some of the most interesting ballets of all time.

Some of these ballets, like The Firebird, Les Sylphides and The Rite of Spring are well-remembered. On the side of the dancers, Anna Pavlova, Tamara Karsavina and Vaslav Nijinsky are perhaps the most revered. However there are many dancers who appeared with the company that are lesser-known in the modern day, and today I’d like to look at three of them.

Stanislas Idzikowski (1894-1977)

Idzikowksi was born in Warsaw, Poland. At the time Warsaw was part of Congress Poland, which were the ethnically Polish lands ceded to Russia by France following the Napoleonic Wars. His teachers included Enrico Cecchetti, Anatole Vilzak and Stanislav Gilbert.

He moved to England at age sixteen, and began to work on the stage. He then danced with the company of Anna Pavlova before joining the Ballet Russes in 1914. He’d dance with the Ballet Russes from 1914-1924, took a break, and rejoined the company soon after.

As a dancer, Idzikowski was not only a good technician, but a good actor, which reflects in the roles he danced. After Vaslav Nijinsky left the Ballet Russes, the roles he originated and defined had to be spread amongst the male dancers of the company. While reviewers noted that the spirit of Nijinsky was missing (as happens when roles are passed on), Idzikowski stepped into the playing field and batted very admirably.

Among the roles he danced with the Ballet Russes were:

- La Boutique Fantasque, one of the most popular ballets, in which a large majority of the characters are toys. Choreographed by Léonide Massine and premiered in 1919, Idzikowski originated the role of The Snob, who dances a comedic variation with The Melon-Hawker.

- Another Massine ballet he originated a role in was Contes Russes, a 1919 ballet based on Russian folklore and fairytales. Idzikowski danced the role of the cat.

- Harlequin in Mikhail Fokine’s Le Carnaval, a role he danced in the 1918 London revival opposite Lydia Lopokova as Columbine.

- Massine’s ballet Le Chant du Rossignol, with music by Igor Stravinsky, premiered in 1920, with Idzikowski performing the role of the Mechanical Nightingale.

- Battista in Massine’s Les Femmes de Bonne Humeur, another original role. One half of a B-couple, Battista has a variation full of entrechats, and takes part in some of the witty dances that build the comedy of the ballet.

- The title role in Petrushka, which, like Le Carnaval, was a role originally danced by Vaslav Nijinsky.

- Massine’s Pulcinella was based on Italian Commedia dell’arte, similarly to Petrushka. Caviello was another original soloist role for Idzikowski.

- The Cavalier of the Lilac Fairy and the Bluebird in the Ballet Russes’ production of Sleeping Princess (Sleeping Beauty), which premiered in November 1921.

- The Spanish-inspired Le Tricorne, or The Three-Cornered Hat was choreographed by Massine with scenery and costumes by Pablo Picasso. The role of The Dandy was originated by Idzikowski.

From 1929-1930 Idzikowski toured the British ‘provinces’, alongside fellow Diaghilev dancers Vanda Evina and Vera Sevina. The three had all appeared at the London Coliseum in Léonide Massine’s The Roses in 1924 (as did Lydia Lopokova), and Evina (1891-1966) and Idzikowski were romantic partners. While it was advertised as ‘Russian Ballet’ the companies’ stars weren’t all that Russian, with dancers highlighted in a review including Phyllis Stickland, Juliette Phillimore and Topsy Harries. Australian soprano Greta Callow provided vocal accompaniment to some of the pieces, and conductor Angel Grande picked up his violin for a solo, as did William A. Scott, the pianist.

Newspaper records show they appeared at the Victoria Rooms in Bristol from the 3rd-5th October 1929, and then at the Victoria Hall, Hanley, Stoke-on-Trent at the beginning of December. Performances were held at the Gloucester Hippodrome from the 5th-10th May 1930, then were at Tunbridge Wells Opera House for the week beginning the 27th May. The following week, the 2nd-7th June were spent at Margate Hippodrome. By September they were in Manchester, performing at the Opera House there from the 16th-27th. The month of September finished at Cheltenham Playhouse. Mid-November was spent in Scotland, performing at the Perth Theatre.

Their repertoire included Ballet Russes standards Les Sylphides and Le Spectre de la Rose, alongside Spring’s Ecstasy, a ballet by Idzikowksi. Phillimore performed a Russian dance, Harries a doll dance, and Stickland a polka. The Bluebird pas de deux was performed, as were two dances titled Chinese and Porcelain, which could be taken from The Nutcracker. A Spanish themed ballet ‘The White Mask‘, an original for the small company, was given in at least Manchester and Perth.

All of these performances were advertised using the names of Diaghilev and the Ballet Russes, showing how great their impact was. Idzikowski is quoted in the Saturday 13th September 1930 edition of the Manchester Guardian:

Our leader is dead, but his spirit remains, and the Russian ballet will go on in the face of difficulties because we are inspired by its great traditions.

Stanislas Idzikowski

During the 1930s Idzikowski (known affectionally as Idzi to his pupils) taught at Sadler’s Wells, guiding the young company and its young dancers. In her autobiography, Margot Fonteyn remembered him as her favourite teacher during her first years at the company, writing that he spoke rather good English with a clipped Polish accent.

Severe but never unkind, he knew exactly what he expected of his pupils and explained clearly how to achieve it. He demonstrated all the steps himself, even in pas de deux class, and he could deftly swing one into a lift supported with only one arm. What incredible strength and knack to partner, so airily, lumpy teenagers taller than himself! Forty years later he is still as slim and precise as ever, his face scarcely changed at all. I do not remember ever seeing him without a waistcoat to his neat grey suit.

Margot Fonteyn on Idzikowski, Autobiography, P52

Idzikowski would teach with Vanda Evina as his accompanist. By 1932 he could be found at 44 Bernard Street, Russell Square. That section of the road, according to Google Maps, today is home to a Pret A Manger and a Tesco. Which is pretty par for the course for London.

But back to Idzikowski, who did still dance. Frederick Ashton’s Les Rendezvous premiered on the 5th December 1933, danced by the Vic-Wells Ballet, and Idzikowski originated a role in it, dancing a variation and a pas de deux opposite the Wells’ leading ballerina Alicia Markova. He also reprised his role of Harlequin in Le Carnaval, which the Vic-Wells danced for the first time on the 24th October 1933, alongside the Bluebird in the truncated version of the final act of Sleeping Beauty, titled Aurora’s Wedding.

In 1934 he appeared in the revue Why Not Tonight?, which was directed by Romney Brent. Ballets for this revue were choreographed by Agnes de Mille, later known for choreographing works including the ballet Rodeo and the musicals Oklahoma and Carousel. This revue was performed at the Palace Theatre and Vaudeville Theatre, both in London, alongside other venues.

The same year as the revue, George Balanchine’s ballet The God’s Go A Begging was recorded for television, and Idzikowski starred opposite Lydia Sokolova in the leading roles of the Shepherd and the Serving-Maid. This ballet was originally premiered by the Ballet Russes by 1928. Going further into the world of cinema and television, he also choreographed for the 1935 film Peg of Old Drury.

Mona Inglesby (1918-2006) founded the International Ballet in May 1941, with Idzikowski as the first maître de ballet. This company was instrumental in bringing ballet to more rural areas in Britain, and teamed up with répétiteur Nicholas Sergeyev to stage the classics. Idzikowski produced their productions of Les Sylphides and Le Carnaval.

Idzikowski retired from teaching following Vanda Evina’s death in 1966, having passed down the Cecchetti method to a large amount of students. Perhaps his biggest contribution to teaching was 1922’s A Manual of the Theory and Practice of Classical Theatrical Dancing (Cecchetti Method), a book Idzikowski co-wrote with noted dance author Cyril W. Beaumont. He worked with the Royal Academy of Dance as well, adjudicating both the Adeline Genée Ballet Competition and the Solo Seal exams (the RAD’s highest vocational graded exam).

Alongside Fonteyn, one of his most noted pupils was Celia Franca (1921-2007). Franca founded both the National Ballet of Canada and its associate ballet school. She staged Le Carnaval in 1958, after learning the ballet from Idzikowski.

Idzikowski passed away on the 12th February 1977 at a London Nursing Home.

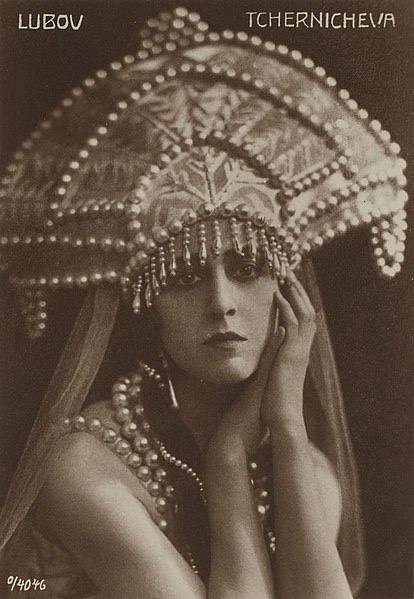

Serge Grigoriev & Lyubov Tchernicheva

The other two dancers I am covering were a married couple, so I have decided to talk through their lives together. Lyubov Pavlovna Tchernicheva was born on the 17th September 1890 in Saint Petersburg, while Serge Lenodiovich Grigoriev was born 120 miles to the East, in the town of Tikhvin, in 1883.

Both of the pair trained at the Imperial Ballet School in Saint Petersburg. Grigoriev graduated in 1900, while Tchernicheva graduated in 1908, in the same class as Bronislava Nijinska. As was custom, they joined the company upon their graduation.

Grigoriev joined the Ballet Russes for their groundbreaking first Paris season in 1909, the same year he and Tchernicheva married. He’d also serve as the Stage Manager for the company. A son, Vsevolod, was born the following year, and Tchernicheva danced with the Ballet Russes for the first time in 1911.

Grigoriev’s repertoire was less recorded than Tchernicheva’s, as a lot of the parts he danced were character soloist roles, including:

- La Boutique Fantasque, Massine’s ballet, in which he originated the role of the Russian Merchant.

- As mentioned above, Le Chant du Rossignol premiered in 1920. Grigoriev originated the role of the Emperor.

- Fokine’s Le Coq d’Or premiered in Paris in 1914. Grigoriev originated the role of Guidone.

The work he did as Stage Manager must be spoken of, as it was just as important as his dancing. He proved a reliable assistant to Sergei Diaghilev, and kept the troupe running, and the repertory rehearsed, across multiple continents.

Tchernicheva’s roles included:

- Calliope in George Balanchine’s Apollo (or Apollon Musagète). One of the last ballets by the Ballet Russes (premiered in 1928), Tchernicheva originated one of the three muse roles.

- A Soloist Role in the Chanson Dansée and Finale of Bronislava Nijinska’s Les Biches. This was another role originated by Tchernicheva, and in both dances she danced alongside others.

- Similarly to Idzikowski, Tchernicheva also originated a role in Massine’s La Boutique Fantasque. The Queen of Clubs is one of the dolls that comes to life.

- The sets for Fokine’s 1909 ballet Cléopâtre were destroyed in a fire in 1917, and new designs were created for the 1918 revival, in which Tchernicheva

- Swan Princess in Massine’s Contes Russes. Tchernicheva originated the role in this 1919 ballet, which tacked ballets inspired by Russian folk-tales together.

- Constanza in Massine’s Les Femmes de Bonne Humeur, a role she originated in 1917.

- The Princess in The Firebird. The Princess, also known as the Tsarevna, is the character who Ivan Tsarevich falls for.

- Alongside Felia Dubrovska, Tchernicheva premiered one of the Two Ladies in Balanchine’s The Gods Go A-Begging, another late Ballet Russes work.

- Prudenza in Massine’s Pulcinella. Prudenza is one of the leading characters, and was the part Tchernicheva danced at the 1920 premiere.

- Zobeida in Fokine’s Scheherazade. Dance writer and historian Cyril W. Beaumont noted her portrayal of Zobeida was the best he’d seeen.

- The title role in Fokine’s Thamar, a role originally danced by Tamara Karsvaina. A wooden figure of Tchernicheva represents her in this role, and is held in the collections of the V&A Museum.

- The Miller’s Wife in Massine’s Le Tricorne. This ballet premiered in 1920 with Karsavina originating the role, and Tchernicheva was among the dancers who succeeded her.

- The Emerald Fairy in Balanchine’s The Triumph of Neptune. This was one of Balanchine’s earliest ballets, and one I’ve done a write-up on previously.

Tchernicheva took on another role in the mid-1920s: that of a teacher. Cecchetti was slowing down his teaching, and was appointed Head of the La Scala school in Milan for the last few years of his life. Tchernicheva stepped up as he slowed down, and she’d continue to teach after the death of Diaghilev in 1929.

The death of Diaghilev signalled the end of the Ballet Russes, but multiple successor troupes would appear. Grigoriev and Tchernicheva would be associated with the Ballet Russe de Monte-Carlo and the Original Ballet Russe. These two companies began their life as one, but a falling out between the Director, Wassily de Basil, and the Artistic Director, René Blum, split the companies into two in 1936.

The pair would continue with de Basil’s Original Ballet Russe, staging the Diaghilev-era repertoire and providing an invaluable link between the old and the new. They reprised some of their old roles, Tchernicheva most often. An Original Ballet Russe programme I own from 1947 lists Grigoriev as the Regisseur General, which means his duties were similar to that of his Stage Manager role.

In 1954 The Firebird was produced by the Royal Ballet, with Margot Fonteyn and Michael Somes in the leading roles. While the original Firebird Tamara Karsavina would coach, Grigoriev and Tchernicheva would stage the ballet. Three years later they’d do the same with Fokine’s Petrushka, originally danced in 1911. Tchernicheva was also teaching company class at the time. Like with Idzikowski, Margot Fonteyn paints a vivid picture of the pair in her autobiography.

Serge Grigoriev was known as a stern disciplinarian for Diaghilev, and his wife I had seen dancing Zobeide in Scheherazade…I had also seen her dance Thamar…She was magnificent in both ballets, and not unnaturally I was expecting a very majestic lady whose commands must be instantly obeyed. What a surprise to find two adorable elderly people, utterly devoted to each other, Grigoriev tall and gentle of expression, Tchernicheva with the beak nose but docile eyes….They never raised their voices, and prefaced every instruction with ‘Please’ or ‘Would you mind?’.

Margot Fonteyn, Autobiography, P143

Grigoriev died in 1968, at the age of 84, in London. His memoirs, detailing his time with the Ballet Russes, had been published in 1953. Tchernicheva died in Richmond, London, in 1976, at the age of 85. Their son Vsevolod, married dancer Tamara Grigorieva, who danced with the Original Ballet Russe. Among Tamara Grigorieva’s roles was Constanza in Les Femmes de Bonne Humeur, a role originated by Tchernicheva.

All 3 dancers, Idzikowski, Grigoriev and Tchernicheva, kept the spirit of the Ballet Russes alive after the death of Diaghilev, as did many other dancers who had danced with the company. The work they did to preserve and stage this repertoire gave new audiences a chance to see legendary works, and shows the continued influence of the Ballet Russes in the wider world of dance.

Sources

Beaumont, Cyril W. (1956). The Complete Book of Ballets. Putnam, London, England.

Haskell, Arnold & Richardson, P.J.S (2010 reprint, originally 1932). Who’s Who in Dancing: 1932. Noverre Press, Hampshire, England.

Fonteyn, Margot (1976). Autobiography. Alfred A. Knopf, New York, USA.

Cecchetti International Classical Ballet page on Idzikowski: https://cicb.org/stanislas-idzikowski/?v=893f26889d1e

A Drawing of Vanda Evina with information on The Roses, 1924: https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1111046/drawing-knight-laura-dame/

Frederick Ashton Foundation page on Les Rendezvous: http://frederickashton.org.uk/rendezvous.html

Cadbury Research Library page on Why Not Tonight?: https://www.calmview.bham.ac.uk/Record.aspx?src=CalmView.Catalog&id=XMS38%2F5212

Pingback: Spotlight On: Pauline Montessu | Theatre Journeys