Among my collection I have several programmes from the Ballet Theatre’s (now American Ballet Theatre) 1946 tour to England. The company performed at the Royal Opera House in the Summer of 1946, one of the first tours to England by a company following World War II.

The ballets featured on the programmes I have are a mix of works that are well-known today, and works that aren’t. George Balanchine’s Apollo is still performed, and the Black Swan and Nutcracker Act II Pas de deux are still obviously featured in their respective full-length ballets. Antony Tudor’s Jardin aux lilas is a little less known, but is still spoken of in dance circles, and performed every so often. And then there’s a couple of ballets that were completely new to me. One of them is today’s topic: 1944’s Tally-Ho, or The Frail Quarry.

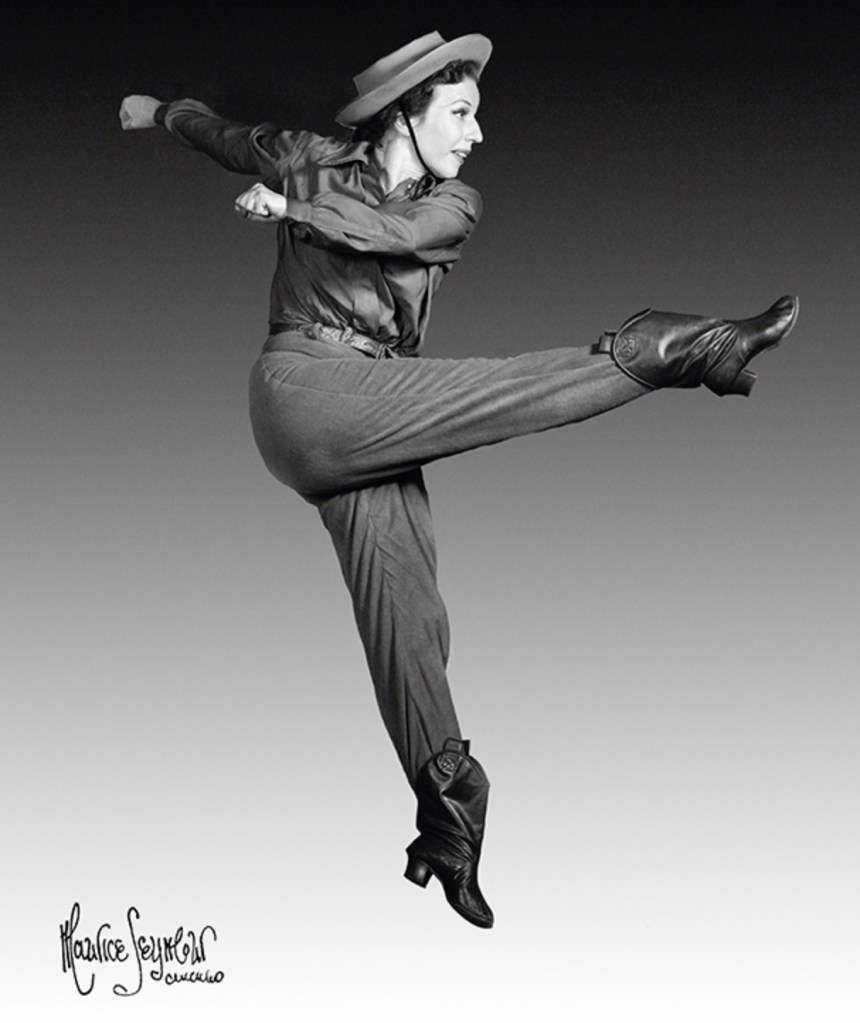

Agnes de Mille

In the early 1940s, the Ballet Theatre, now known as American Ballet Theatre, began to tour the USA. The company had been founded in 1939, with Richard Pleasant (1906-1961) directing the first season and Lucia Chase (1897-1986) becoming the company’s founding ballerina. Chase had previously danced in the company of Mikhail Mordkin, a former partner of Anna Pavlova. The fledgling company aimed to build a repertoire of the old Russian/Ballet Russes classics, alongside newer American works.

…[Richard] Pleasant was ordering the choreographers by the gross; cables went to every quarter of the world. One had only to say idly “I once heard of a ballet about an omnibus” to have Richard note the choreographer’s name and, if alive, his telephone number…when assembled there were ten ballet choreographers on the staff – [Mikhail] Fokine, [Mikhail] Mordkin, [Adolph] Bolm, [Bronislava] Nijinska, [Anton] Dolin, [Antony] Tudor, [Eugene] Loring, José Fernandez, Andrée Howard, de Mille.

Agnes de Mille, Dance to the Piper, p.252

One of the choreographers hired for the company’s first season was the aforementioned Agnes de Mille (1905-1993). De Mille was the niece of filmmaking superstar Cecil B. DeMille, and had worked with Marie Rambert’s Ballet Club in the 1930s. This London-based company provided many talented choreographers with early experience; Antony Tudor and Frederick Ashton also worked with the company.

After returning to the USA de Mille prepared a ballet for the Ballet Theatre’s first season. Richard Pleasant had pushed her to prioritise choreography over dancing, and in retaliation de Mille aimed, in her own words, to create a work that was ‘as surprising as possible’. This work, Black Ritual, premiered in January 1940, and was unique in the fact that it used African-American dancers. The representation of people of colour in majority-white ballet companies was rather rare, and Black Ritual, while not a success, was significant in this regard.

The ballet, Black Ritual, hardly had a chance. It was danced at its premiere at a pace calculated to kill all excitement…with time and recasting all faults could have been put right, but there was no time. The schedule was stuffed with premieres; we were allocated three performances only…After the three week season my girls were dispersed and the work has never since been performed.

Agnes de Mille, Dance to the Piper, p.257

De Mille created one of her first big successes, Rodeo, for the Ballet Theatre’s rival. The Ballet Russes de Monte Carlo danced Rodeo for the first time on the 16th October 1942. Though American in theme, critic Edwin Denby praised the company for understanding the American style of movement. He also praise de Mille’s choreographing, writing they were ‘the best we’ve had on the prairie subject, and the best Miss de Mille has done’.

The success of Rodeo led to an even bigger success for de Mille: Oklahoma!. The first musical by Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein II, the original Broadway production, choreographed by de Mille, ran for over 2,000 performances from 1943-1948. The first act of the musical ends with a dream ballet, thought to be the codifier for the trope.

de Mille would go on to have a career full of success, choreographing both ballets and musicals, along with the 1955 film adaptation of Oklahoma!. In 1947 she won the inaugural Tony Award for Best Choreography (for Brigadoon), and would win another for Kwamina in 1962. In 1986 she was awarded with the National Medal of Arts, the same year as Rodeo composer Aaron Copland. Some of her works are still performed today, and her choreography has been influential. But some have been forgotten, like Tally-Ho.

Tally-Ho

When I first saw the title of this ballet, I thought it would have a Western theme, similar to Rodeo. However the ballet is actually set in a French forest during the time of Louis XVI. The featured characters are a husband and wife, a Prince, and four other women, who are categorised by their morals (A Lady, no better than she should be; Two others, somewhat worse; and the innocent).

Like most of her works at the time, de Mille choreographed Tally-Ho in her two-room New York apartment. Paul Nordoff (1906-1977) arranged the music, bringing together pieces by Christoph Willibald Gluck (1714-1787). Pioneering theatrical lighting designer Jean Rosenthal (1912-1969) lit the ballet.

The design for the ballet was done by the Motley design group. This was a group established by three British women: Margaret Harris (1904-2000), her sister Sophie Harris (1900-1966), and Elizabeth Montgomery (1902-1993). Margaret and Elizabeth spent the Second World War in America, while Sophie remained in Britain, so it is likely the former two had the biggest hand in the ballet’s design.

The characters in the ballet are:

- The Wife, danced at the world premiere by de Mille herself. Edwin Denby described her performance in the role as ‘wonderfully real’. Janet Reed (1916-2000) would later dance the role, as would Shirley Eckl, who performed the role during the 1946 London Tour. Carmen de Lavallade (b.1931) danced the role in the premiere of the 1965 revival.

- The Husband, a role originated by Hugh Laing (1911-1988). Laing was the partner of Antony Tudor, and had accompanied him to America for the Ballet Theatre’s first season. He performed a wide range of roles, and was still performing this role during the 1946 London Tour. Dmitri Romanoff (1907-1994) also danced the role in 1946, and Royes Fernandez (1929-1980) took the role at the premiere of the 1965 revival.

- The Prince, originally danced by Anton Dolin (1904-1983). Dolin was the frequent dance partner of Alicia Markova, and co-founded the English National Ballet with her. He danced with the Vic-Wells Ballet, the Ballets Russes, and from 1940-1946 the Ballet Theatre. John Kriza (1919-1975) danced the role in 1946, and returned to the role for the 1965 revival.

- The role of A Lady, No Better Than She Should Be was originated by Maria Karnilova (1920-2001). Karnilova had joined the Ballet Theatre it its very early days, and would go on to have a successful Broadway career, notably winning the 1965 Tony Award for Featured Actress in a Musical for her role as Golde in Fiddler on the Roof. Muriel Bentley (1917-1999) was performing the role in 1946, and Sallie Wilson (1932-2008) in 1965.

- Two Others, Somewhat Worse were roles first danced by Bentley and Miriam Golden. Barbara Fallis (1924-1980) was dancing one of the women in 1946, alongside future New York City Ballet principal Melissa Hayden (1923-2006). In 1965 the roles were danced by Barbara Remington and Veronika Mlakar.

- The Innocent was the role originated by Lucia Chase herself. Denby called this role one of Chase’s ‘most subtle’, and she was still dancing the role in 1946. Original Oklahoma! cast member Bambi Linn (b.1926), who was a guest soloist with the Ballet Theatre, also performed the role. In the 1965 revival the role was performed by Karen Krych.

The cast was rounded out by an ensemble of 11 courtiers.

In his review of the New York premiere in April 1944, Denby described the plot in a brief summary.

…the lively young people of the court amuse themselves…Among the guests is a serious young man…he loves his wife and he loves to read. The atmosphere doesn’t trouble him, but it troubles her. The Prince, a very grand young man indeed, sees her, follows her, finally meets her alone. She returns to her husband, and the charm goes out of the afternoon. He slaps her, gently but clearly. Finally an innocent girl who just came to court that day reconciles them, and the Prince grandly bows out.

Review by Edwin Denby, compiled in Dance Writings, p.211

Tally-Ho premiered on 25th February 1944 at the Philharmonic Auditorium in Los Angeles, California. The New York premiere, at the Metropolitan Opera House, came two months later. Denby wrote that the ballet was ‘not quite a hit, but it was certainly not a flop’. He praises the farcical elements, but comments there was not quite enough serious dancing to provide a contrast.

The ballet stayed in repertoire through 1944 and 1945, and was among the ballets brought over for the 1946 London Tour. Reed took over the role of the Wife quite soon after the ballet’s premiere, presumably because de Mille was busy and in demand. Sometime in the late 1940s the ballet was filmed by Victor Jensen. This cast featured Reed and Laing as the Wife and Husband, Kriza as the Prince, Linn as the Innocent and Bentley as the Lady No Better Than She Should Be. The film sits today in the New York Public Library.

Or, The Frail Quarry

In 1965, the ballet was revived. This time, it was performed under the title of The Frail Quarry. The premiere of this revival was on the 2nd April 1965, at the New York State Theater. Again, however, it was not a smash success. De Mille doesn’t touch much on the ballet in her 1952 autobiography, and even today, when articles are written about preserving de Mille’s works, Tally-Ho is mentioned a lot less than some of her other ballets.

On the 9th January 1986, Lucia Chase passed away. A few months after her death, her friends gathered to pay tribute at the Bruno Walter Auditorium in Lincoln Center, New York. Among those friends were Agnes de Mille, and some of her words were recorded in her son Alexander’s (1931-2017) book. And surprisingly, it’s here we find mention of Tally-Ho.

In April 1944, Tally-Ho, my ballet, was having its New York premiere at the Met. I was nervous as hell, and Lucia, who was in Tally-Ho, let me use her dressing room…When I sat down at my table – now remember the date, 1944 – I noticed a small flower box, and it contained a large bunch of violets. Very beautiful, old-fashioned ones, with a handwritten card – from my husband who was overseas fighting the war…I said “Lucia, this is from my husband.” She looked at me with great wide eyes. “How wonderful!” she said and the tears poured down her cheeks. Then we went on with our makeup.

Bravura!: Lucia Chase and the American Ballet Theatre, p.323

In their online biography of de Mille, the De Mille Working Group write that, shortly before her death, de Mille went back to working on Tally-Ho, aiming to revise it. In particular, she wanted to change the ending, having never been happy with it. Sadly, this would not come to fruition. Agnes de Mille died on the 7th October 1993.

So Why Was it Forgotten?

Following a choreographer’s passing, one is sadly able to predict that many of their works will be forgotten, as previous entries in this series has shown. This is the newest ballet that I have looked at, having premiered 18 years after the second-newest, George Balanchine’s The Triumph of Neptune. Both choreographers were incredibly influential in American dance. And both have works that have been forgotten.

I doubt Tally-Ho was a terrible ballet. Living in England, I have obviously not been able to go to the New York Library for the Performing Arts to view the film, but I am convinced it would not be a waste of 46 minutes. The ballet lasted years in the repertoire, had a revival, it couldn’t have done that badly. While it perhaps wasn’t de Mille’s best work, it did not deserve its fade into obscurity.

It’s also interesting to ponder on what the ballet’s reputation would be today if Agnes de Mille had completed those revisions in the 1990s, and another revival had premiered. Would the designs have been as opulent? Which dancers would’ve been cast? And would Agnes de Mille finally have been happy with the ending? I like to hope she would’ve been.

Sources

De Mille, A. (1952). Dance to the Piper. Little, Brown and Company.

Denby, E. (1986). Dance Writings. Dance Books.

Ewing, A.C. (2009). Bravura!: Lucia Chase and the American Ballet Theatre. University Press of Florida.

De Mille Working Group: https://www.agnesdemille.com/short-biography-of-agnes-de-mille-1

The NYPL online record for the film of the ballet: https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/aaef4be0-f879-0130-3faa-3c075448cc4b