In December 1884 London’s Empire Theatre premiered a new production of the classic ballet Giselle. The theatre had only opened in April that year, but, alongside some shorter divertissements, the theatre had already produced a production of the ballet Coppélia, the first production staged in London. Both of these ballets would be staged by the theatre’s Maître de ballet Aimé Bertrand, and would be presented with a large cast (around 60 for Coppélia and 100 for Giselle). However neither production would last long in the repertory, and they remain minor blips in the history of the two ballets.

Among my collection is a programme from Boxing Day 1884 (see here), showing the ballet with the preceding opera and pantomime sketches. Having this programme led me to research the dancers of this production further, and I’d like to share my findings in this post.

Giselle: Alice Holt

Alice Holt had danced Swanilda in the Empire’s production of Coppélia, so it was a no-brainer that she would dance Giselle’s titular role. She was an established performer who from what I can find first pops up in England in September 1877, performing at Paul’s Concert Hall in Leicester. This venue was run by a Mr. W. Paul, and Alice appeared there with the company of Mademoiselle Esther Austin.

Austin was an acclaimed dancer and pantomimist, and Alice was one of the premiere danseuses in her troupe. They performed in Manchester in October and Dublin in November, with Alice being highlighted as a ‘young, charming and accomplished artiste’ (The Era, 4th November 1877). The same newspaper describes her as being from the Grand Théâtre, Amsterdam, so it is possible she had appeared abroad in the past.

From December 1877-January 1878 she starred in the pantomime The Forty Thieves at the Alexandra Opera House in Sheffield, receiving positive reviews. The Sheffield Daily Telegraph (22nd January 1878) wrote ‘Miss Holt’s graceful and marvellously swift and brilliant movements place her high above what is usually seen in pantomime’, while the Sheffield and Rotherham Independent (15th January 1878) described her as ‘perhaps unequalled in her profession’.

In the tail end of the decade Alice’s star continued to rise, with multiple engagements in various London Theatres. She spent the Christmas season of 1878-1879 in Leeds Grand Theatre’s pantomime Bluebeard, and in September 1879 began starring in The Rhine and the Rhino at the London Pavilion opposite well known music hall performer Nelly Power. Both Alice and Nelly then moved over to the Canterbury Theatre of Varieties for the Christmas season, starring in Peri of Peru.

Peri of Peru ended its run in May, but Alice stayed at the Canterbury for their new ballet Nymphs of the Ocean, which continued until Autumn 1880. The next Christmas season Alice spent in Birmingham in Little Red Riding Hood, once again receiving good reviews. By June 1881 she was back dancing in London, and became associated with the Martinetti Company.

The Martinetti company was run by Paul Martinetti, a French-American acrobat and pantomimist, and his brother Alfred was also a member of the compay. They presented sketches and pantomime dramas, becoming popular in English music halls. Alice was billed separate from the company in June 1881, but by August she was listed amongst the company when they performed their version of The Magic Flute.

A sign that Alice’s reputation was growing was her engagement in a London pantomime – Little Bo-Peep, Little Boy Blue and the Little Old Woman that Lived in a Shoe at the Theatre Royal Covent Garden, known today as the Royal Opera House. Alice took part in a grand ballet during the show, and was praised for her performance.

The early 1880s continued much in the same fashion, with Alice consistently booking engagements in London variety theatres. Another large success came with 1883’s A Silver Wedding, which Alice starred in at the Canterbury, and with Olympus at the same theatre in Spring 1884. This brings us to the Empire, and Coppélia.

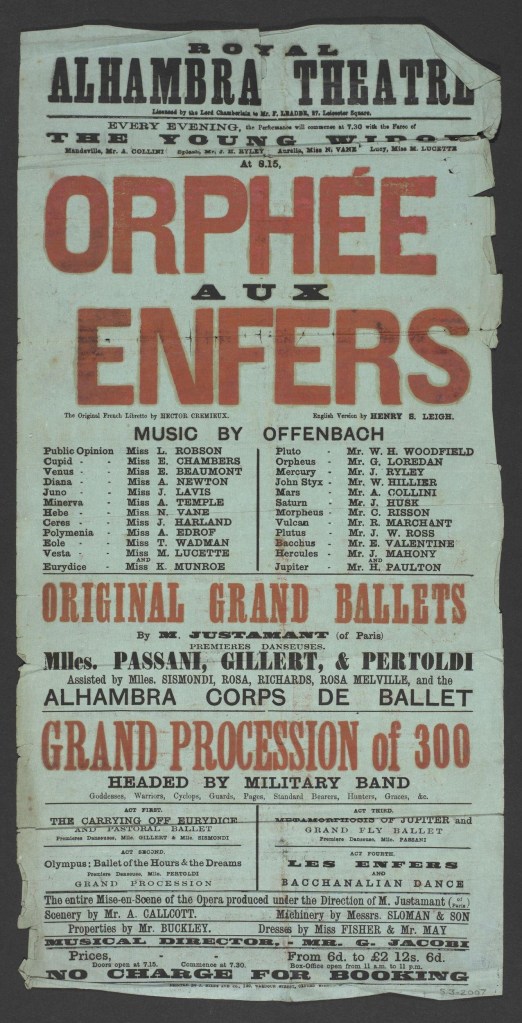

Alice received good reviews for the role of Swanilda, particularly being praised for her mime. However, the ballet was last on the Empire’s bill, which meant a fair amount of the audience had already left before the ballet had begun. The Empire Theatre’s rival Alhambra, presented two ballets during their bill, something the Empire would later do, but this was one of their earliest ballet productions. As such, despite the positive reviews, the ballet was only performed for just over a month.

London audience had seen the original Giselle, Carlotta Grisi, in 1842, and nearly 40 years later there were reviewers who still remembered her performance. Luckily for Alice, she was deemed a worthy successor in the role. The worst anyone had to say about her was that her skirt was too short, as a reviewer in the Daily Chronicle (27th December 1884) noted she was ‘expert in her dancing’ but ‘audacious in her dressing’.

Giselle had an even shorter run then Coppélia, being gone from the bill by mid-January. This also marked the end of Alice’s short association with the Empire, and she moved over to the Gaiety Theatre to star in a new ballet there, taking along with her her Albrecht and her Hilarion. By October 1885 she was starring in The Magic Cave at the Royal Music Hall in Holborn. This show was advertised as an ‘electrical musical interlude’ (The Globe, 13th October) and starred Harriet Laurie, the ‘Electric Star’.

In June 1886 she danced in the opera Carmen at Drury Lane. The dances for this production were arranged by Katti Lanner, who would go on to spend two decades at the Empire as their Ballet Mistress. Alice and Lanner both then participated at the Christmas show at the Tyne Theatre in Newcastle. Lanner arranged the dances for The Fair One with the Golden Locks and Alice danced in the piece.

The newspaper trail for Alice runs cold after that, and is not helped by the slew of references to Alice Holt Forest in Hampshire. A reference to what I believe is our Alice comes from the London and Provincial Entr’acte from 26th August 1893. The writer makes reference to an Alice Holt who was ‘a good-looking and graceful danseuse’ ten years ago (so 1883), which fits our Alice well. Unfortunately the writer is reporting on the suicide of Miss Issy Holt, who he believes (‘if I mistake not’) was sister to Alice. Issy Holt was a stage name for a Mrs Isabel Tyrell (also spelt Tyrrel and Tyrrell). One obituary mentions a sister named Florrie but there are no other mentions of an Alice. What this does definitively tell us, was that by this point our Alice was off the stage, and probably had been for some time if the writer had to describe her.

Albrecht: Miss Sismondi

In this production of Giselle, Albrecht is mostly referred to as Loys. This was the name Albrecht used to disguise himself in the early productions, but this detail is dropped from many modern productions. The role was also danced by a woman just as it was in Paris at the time. Miss Sismondi had previously danced Franz in the Empire’s Coppélia, so like with Alice Holt it made sense for her to dance the male lead here.

The name Miss Sismondi would indicate foreign origin, if not for the fact that it was a stage name. Her real name was Betsy Simmons, daughter of a china dealer. She had been a student of the noted dancer and family patriarch Léon Espinosa. The Espinosa family had a long association with the Alhambra Theatre, the Empire’s rival, so it was not a surprise to learn that Miss Sismondi was engaged as a member of the company there too.

At the time of her first mentions in newspaper reviews, December 1867, she was appearing as the principal dancer in The Golden Plumes. This ballet premiered on December 23rd, and Sismondi received positive reviews. A writer in The Era (29th December) believes that the 23rd was Sismondi’s debut at the Alhambra, which may very well be the case.

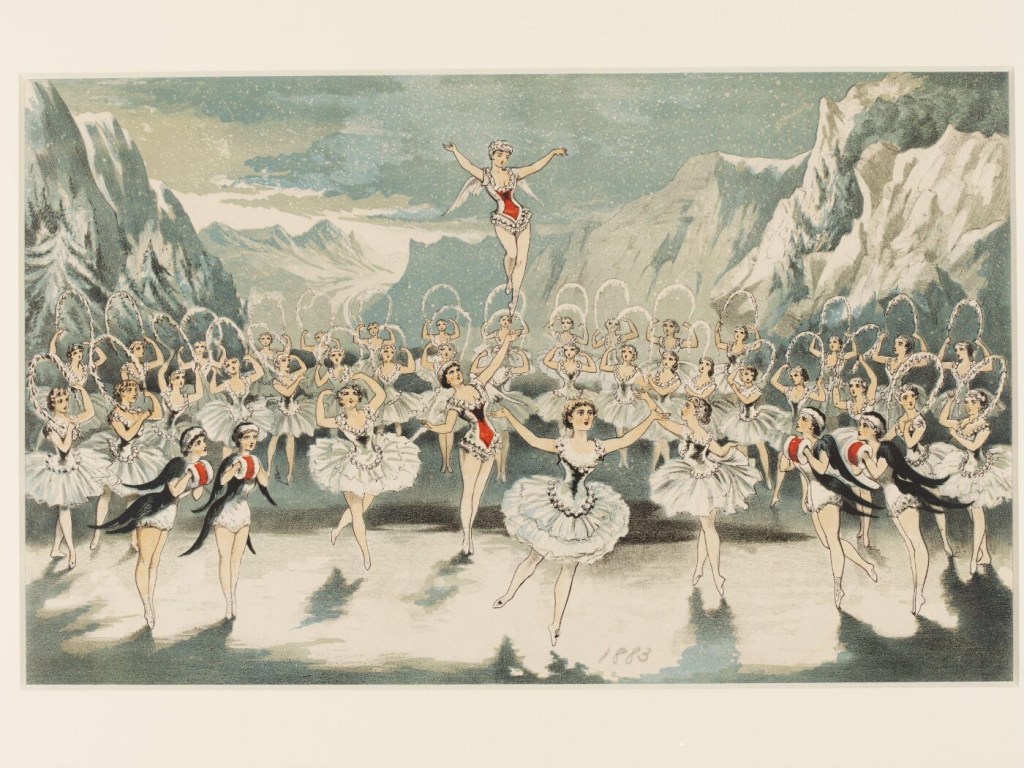

By March 1868 she was starring in Mabille in London, in which she danced the role of a flower-girl and had a solo. She followed this up with The Mammoth Waterfalls (June 1868), a ballet in which the seemingly compulsory Alhambra rule of spectacle was fulfilled by the creation of real waterfalls on the stage. A review from Bell’s Life in London (20th June) notes that Sismondi’s solo was ‘intricate and difficult’ but ‘executed with great ease and grace’.

Sismondi continued at the Alhambra in 1869, dancing roles in The Fairy Acorn Tree, The Spirit of the Deep, and Coming of Age, having the leading role in the latter. In December that year she began appearing at the newly-opened (the first theatre on the site was lost to fire) South London Palace of Amusement. She appeared at the theatre’s opening night on the 19th December, starring in their Grand Ballet.

An Easter ballet, The May Queen, was staged in Spring 1870 with Sismondi taking the a leading role, and was still on the bill in June. The Descent of Apollo and Revels of Bacchus was staged in the Summer, continuing for the rest of the year. Sismondi danced Flora, being noted by critics for her gracefulness as a dancer.

By July 1871 Sismondi was back at the Alhambra, dancing in their new ballet The Beauties of the Harem. This work was described as an ‘elegant divertissement’ in newspaper adverts, and Sismondi was given top billing. Sismondi’s back-and-forth attitude with the Alhambra begins to properly show here, as in June 1872 she was starring in Jacques Offenbach’s Genevieve de Brabant in Liverpool, dancing in a new ballet added to the opéra bouffe. This production then toured to places like Leicester and Stockton-on-Tees.

She was back in London by August dancing at the Metropolitan Music Hall, and spent the Winter season of 1872-1873 in Dublin, Ireland, playing Columbine in the Theatre Royal’s Harlequinade. This arrangement continued in 1873, where she spent most of the year at the Metropolitan and Winter in Dublin. Her next return to the Alhambra came in June 1875, this time to star in the new ballet Cupid in Arcadia.

Sismondi remained at the Alhambra for most of the late 1870s, sometimes doing short engagements elsewhere. A large success came with 1877’s Yolande, in which Sismondi danced a supporting role. Part of her time spent away from the Alhambra may have been because of this – perhaps she preferred being the leading ballerina elsewhere than a soloist at the Alhambra. While she did get leading Alhambra roles, they never seemed to be in the ‘main ballet’, and if they were she’d step in as a replacement after another ballerina left.

In 1882 she starred in Pluto at London’s Royalty Theatre, and made her debut at a newly-opened theatre, the Novelty, in December 1882. Thought she couldn’t have foreseen it, this was a good move, as in the same month the Alhambra burned to the ground. In the early morning of the 7th December a fire was noticed at the theatre, and despite fire engines arriving quite quickly the theatre was destroyed. Two firemen were seriously injured, with one, Thomas George Ashford, dying from the injuries he sustained, and the destruction of the theatre left over 600 performers and stagehands unemployed.

The day after the fire the Directors of the Alhambra committed themselves to rebuilding the theatre, which isn’t that surprising. Many theatres were destroyed in the fire, and during the 19th century the prime way of dealing with the situation was to just build another theatre on the same site. While the rebuilding was taking the place the company performed at Her Majesty’s Theatre, and Sismondi rejoined them in March. She was billed as a ‘second premiere danseuse’, a rank below the 6 premiere danseuses.

The company produced a revival of Jacques Offenbach’s A Trip to the Moon, which they had previously staged in 1876. Sismondi danced one of the Four Swallows in the Snow Ballet alongside the other three second premiere danseuses, Mademoiselles Gerrish, Hemmings and Patti.

There was another brief stint at the Metropolitan in October 1883, but Sismondi remained with the Alhambra Company as they returned home. The rebuilt Alhambra opened on Monday 3rd December with the opera The Golden Ring, in which Sismondi participated as a dancer. This Alhambra stint lasted until March 1884, and then Sismondi moved to the new Empire Theatre.

She was made a première sujet of the Empire’s ballet company and starred in their opening production, Chilperic. This was an operetta, and the supporting ballets were produced by Aimé Bertrand, who had also moved from the Alhambra. No proper full-scale ballets were produced until Coppélia, which brings us to Winter 1884.

Like Alice Holt, Sismondi was praised for her work in both Coppélia and Giselle. Her and Alice then danced in a Japanese ballet at the Gaiety Theatre. The rest of 1885 seems quiet, but she danced in the Grand Theatre Birmingham’s pantomime over the Christmas season. She was billed here as Signora Sismondi, having seemingly upgraded her presentation of herself as a foreigner.

Her career as a dancer seems to slow down a bit in the late 1880s, which is unsurprising considering her longevity. In 1886 she danced in a pantomime in Wolverhampton, and was back in Birmingham in 1887. By 1888 engagements of the ‘Sismondi and Vivian Troupe of Dancers’ appear. The Era (18th August 1888) described the troupe as being made up of four dancers. The troupe performed at variety theatres across London, including some of Sismondi’s old haunts like the Canterbury Theatre of Varieties.

The Sismondi-Vivian Troupe continued into the 1890s, and a break-off group named the Sismondi Troupe of Vocalists and Dancers was established in late 1889. The former Troupe were able to tour South America and Africa alongside their performances around England. An 1893 article in the Bristol Magpie (14th January) describes Sismondi as ‘dark, with the glossy raven tresses of Arabia’, which is perhaps why she was able to pass as Italian. By 1897 she seems to have retired as a dancer.

Unlike Alice Holt, we do know a bit of what Sismondi did after her retirement as a dancer. Her first venture seems to have been working for Mr C. St. John Denton, instructing pupils in pantomime. The Era (14th May) interviewed her in connection with this role in 1898.

She details her history as a dancer, saying that she was dancing at the Alhambra when ‘barely in her teens’, having begun dancing at about 10. She recounts her knee injury, a result of catching her foot in an open groove at the Alhambra. She bemoans the fact that London audiences want to see ‘skirt-dancing’ and gymnasts instead of classical ballet, and seems to feel that many of the dancers in London theatres are wasted. Overall she seems to be a rather determined lady, saying that she wants to teach students who are truly committed to dance.

The Sismondi Troupe/Quartette’s performances continued until 1899. By 1902 Sismondi had left Denton and started giving private dance lessons at 9, Great Newport Street, Westminster. In 1905 she moved to work with John Tiller, founder of the Tiller Girls dance troupe. She was Head of Tiller’s dance school in London where the most promising girls were trained. Her private lessons outside of Tiller’s school also continued.

Her long teaching career seems to have come to a close in the early 1920s. At this point she had trained dancers who worked in all fields of theatre, as well as dancers who became teachers themselves. Her career had spanned decades, and she had left a large mark on ballet in Britain, even if we are not familiar with her name today.

Secondary Sources

Guest, Ivor. (1992). Ballet in Leicester Square. Dance Books.

Pritchard, J. (2001). Collaborative Creations for the Alhambra and the Empire. In Dance Chronicle, 24(1), pp. 58-82. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1568052

Pritchard, J. (2010). A Trip to the Moon. V&A Blog. https://www.vam.ac.uk/blog/diaghilev-and-ballets-russes/trip-moon