French author Alexandre Dumas fils (1924-1895) enjoyed a career that spanned decades, publishing many successful books and plays. One of his most notable works is the 1848 novel La Dame aux Camélias. Inspired by his relationship with courtesan Marie Duplessis, who died of tuberculosis at the age of 23, Dumas fils created the characters of Marguerite Gautier and Armand Duval to serve as the protagonists of his tragic romance.

Dumas fils himself produced a stage play adaptation that premiered in Paris in 1852. In the audience for a performance of this play was opera composer Giuseppe Verdi, whose 1853 opera La traviata was based on Camélias. In this adaptation Marguerite became Violetta Valéry and Armand Alfredo Germont. The opera has gone on to become one of the most performed operas in the world.

Among the myriad of adaptations are a handful of balletic versions. Marguerite, who became known as Camille in American adaptations, has become a role that highlights a ballerina’s dramatic abilities, and for this reason many notable dancers have taken a stab at it. This post will examine just six of these productions, focusing on the ballets created in the mid-20th century.

Camille (1946)

Choreographer: John Taras

Music: Franz Schubert

Company Created For: Colonel W. de Basil’s Original Ballet Russe

Decor: Cecil Beaton

Premiere: 1st October 1946, Metropolitan Opera House, New York City

Length: 1-Act

In 1946 Colonel de Basil’s company made their return to New York City after five years away. They were due to start a tour of the United States that would last until March 1947, when they finished with another week at the Met. Prior to their return to the US the company had been performing in Central and South America, and as such many of their dancers were not known to US audiences. Sol Hurok, the company’s New York impresario, combatted this situation by hiring a roster of dancers the US audiences would know, among whom were Alicia Markova and Anton Dolin.

Markova and Dolin secured fame in both the UK and US, and at this time Markova was renowned as one of the greatest ballerinas in the world. If the 1946 New York Met engagement was to have a world premiere, it only seemed correct that it would be created for her. Choreographer John Taras, who had worked with Markova in the past, chose Dumas fils‘ story to adapt into a ballet.

Apart from Markova and Dolin, who were portraying Camille and Armand, the cast also included Miguel Terekhov (Armand’s Father) and Mattlyn Gevurtz (Nanine, Camille’s Maid). Terekhov had joined the company in 1942 while they were touring in his native Uruguay. Despite playing a Father Terekhov was just 18 when the ballet premiered, 24 years younger than his ‘son’ Dolin. Gevurtz, who was also known by the name Mattlyn Gavers, had just finished a run in the Broadway musical The Day Before Spring. She was not a Ballet Russes dancer, and was most likely brought in after members of the company got stuck in South American following a transportation strike.

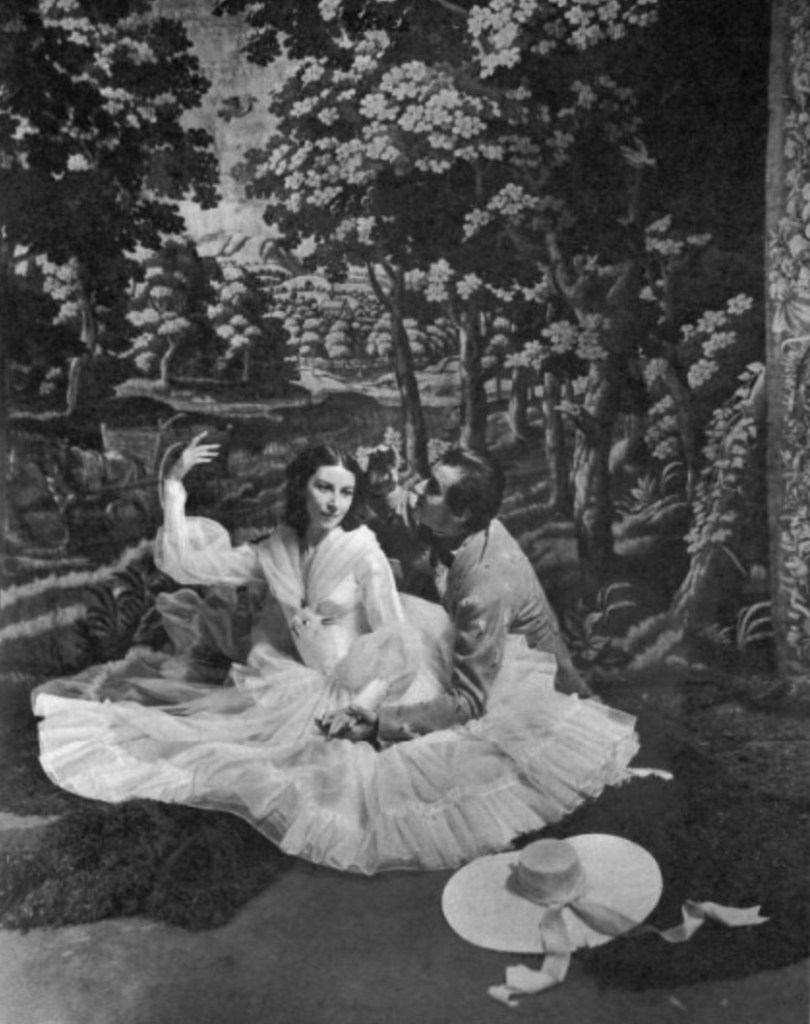

The company managed to arrive in New York the day before the Met Season opened, but in the end Taras’ substitute dancers premiered Camille. The framing for the piece was the same as Dumas fils‘ book, with Camille reminiscing about her romance while on her deathbed. Critics felt that Taras excluded too much from the narrative, meaning there was no chance for the audience to properly connect with the characters. Edwin Denby pointed out that the choreography, while good, was too innocent for the subject matter, meaning the romantic passion between Camille and Armand had no opportunity to prosper. Nevertheless Markova’s performance was highly praised, as were the elegant and opulent designs by Cecil Beaton.

Camille lasted in the repertory of the Original Ballet Russe until the end of March 1947. It is likely Markova and Dolin were the only people to dance their characters, and at the end of the US Tour their guest arrangement concluded. The Ballet Associates, who had commissioned the ballet, took control of the costumes and scenery and donated them elsewhere.

Lady of the Camellias (1947)

Choreographer: Anton Dolin

Music: Giuseppe Verdi

Company Created For: Markova-Dolin Ballet

Decor: Castellano

Premiere: Autumn 1947

Length: Unknown

Camille would not be the only one of these ballets to be danced by Markova and Dolin. After they left the Original Ballet Russe they reestablished their Markova-Dolin Ballet, a company that had existed for some time in the late 1930s. The company was a touring one, and in the 1930s had focused largely on provincial Britain. This time, however, Markova and Dolin would take their art to Latin America, a region that had recently experienced a boom in ballet popularity.

During their time in Mexico the company premiered Dolin’s adaptation of the work, which used the music from Verdi’s La Traviata. This version followed the opera more closely, opening at Camille’s party. The company performed the ballet in both Mexico and the USA, but again it did not last long. Markova and Dolin returned to the Sadler’s Wells Ballet as Guest Artists in the Summer of 1948, and for a short time their company was disbanded.

Though Markova and Dolin reformed their company in 1949, The Lady of the Camellias did not make a comeback. Markova scaled down her appearances with the company in 1951, though did continue to perform roles like Giselle as a Guest Artist. Happily, the final iteration of their company has gone on to become the English National Ballet.

Lady of the Camellias (1951)

Choreographer: Antony Tudor

Music: Giuseppe Verdi

Company Created For: New York City Ballet

Decor: Cecil Beaton

Premiere: 28th February 1951, New York City Center

Length: Ballet in 4 scenes

Remember when I wrote that Cecil Beaton’s costumes and sets from Camille were given to the Ballet Associates? Well the group lent them to the New York City Ballet, who at this time were still a fledgling company. They decided to use these designs for another adaptation, this one a vehicle for Diana Adams and Hugh Laing. Antony Tudor chose the music for the ballet from five of Verdi’s early operas.

The ballet had the same problems as Taras’, with critics finding it to be more of a series of a short vignettes than a narrative, leaving no time to properly know the characters. The pas de deux for Adams and Laing was well-received, but another problem with the work was the lack of dancing, something Tudor acknowledged himself. He only had three weeks to put the ballet together and stated that he felt it wasn’t a ballet he was doing because he wanted to do it – it was simply because they had the costumes and sets for it.

Tudor’s adaptation, like Taras’ and Dolin’s, has not survived in the repertory. A warehouse fire in 1953 destroyed a large amount of costumes and scenery used by the New York City Ballet, and Cecil Beaton’s luxurious designs were among those lost.

Die Kameliendame & La Dame aux Camélias (1957 + 1960)

Choreographer: Tatiana Gsovsky

Music: Henri Sauguet

Company Created For: Deutsche Oper Berlin

Decor: Dupont (Paris production)

Premiere: 1957, West Berlin, Germany

So far we’ve seen two celebrated ballerinas take on the role of Camille/Marguerite, and now another one can be added to the list: Yvette Chauviré. Chauviré had been dancing at the Paris Opera since the 1930s, and by the 1950s was on a contract that allowed her to make more guest appearances. In 1957 she came to Berlin, where Tatiana Gsovsky was creating her own adaptation of Dumas fils‘ novel.

This adaptation is notable for its score, which was created for the work by French composer Henri Sauguet. Sauguet had composed scores for ballets before, notably La Chatte (1927), an early ballet by George Balanchine, and 1945’s Les Forains.

In 1960 Gsovsky brought the ballet to Paris, where it was danced for the first time on the 3rd February. Chauviré once again danced the leading role, partnered by George Skibine, who was at that time both an étoile and the Maître de ballet of the company.

Marguerite and Armand (1963)

Choreographer: Frederick Ashton

Music: Franz Liszt

Company Created For: Royal Ballet

Decor: Cecil Beaton

Premiere: 12th March 1963, Royal Opera House, London

Length: 1-Act (Prologue and Four Scenes)

By the 1960s Frederick Ashton was deliberating on creating a Dame aux Camélias ballet, but was stuck on what music to use. According to his Marguerite Margot Fonteyn, Ashton deliberated over choreographing a ballet to Sauguet’s score, but didn’t find it suitable. He chose Franz Liszt’s Piano Sonata in B minor for the ballet after hearing it on the radio, and it was orchestrated by Humphrey Searle (though Searle’s orchestrations were replaced with Gordon Jacob’s in 1968).

Ashton’s ballet takes the flashback approach, beginning with Marguerite on her deathbed. He worked on the ballet using Dumas fils’ original book, also researching the real-life inspiration for Marguerite Gautier Marie Duplessis. The design of the ballet he entrusted to Cecil Beaton, who, as we have seen, had experience with costuming Camilles and Marguerites. He had also worked with Ashton in the past. Fonteyn remembered that she was loathe to wear red camellias as part of her costumes, because in the novel Marguerite wears them to signify she is menstruating and unable to take a love. As such, Beaton’s red dress is adorned with a white flower.

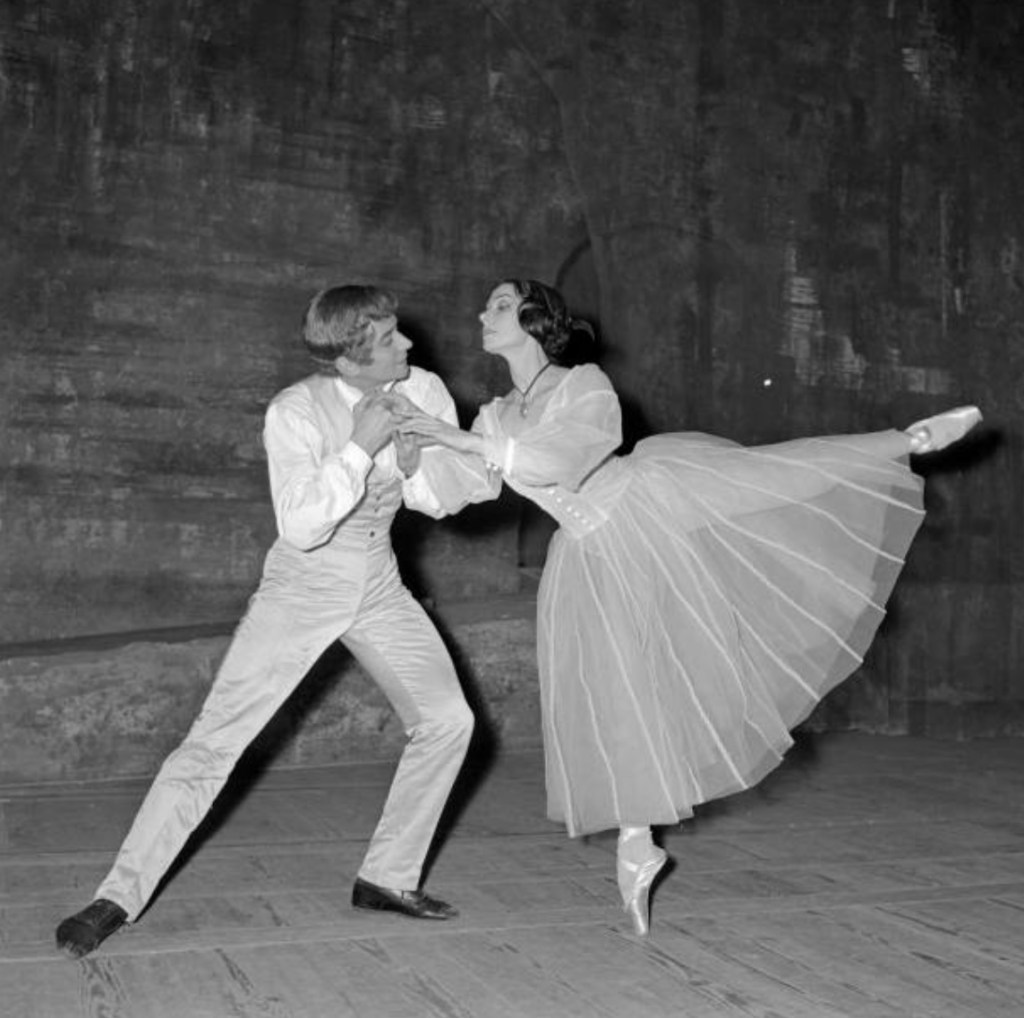

In 1962 Margot Fonteyn had found a new partner in Rudolf Nureyev, who would dance opposite her as Armand. Michael Somes, Fonteyn’s partner of the 40s and 50s, would portray Armand’s Father. The ballet took little rehearsal to actually put together, but was delayed from late 1962 to March 1963 due to the touring commitments Fonteyn and Nureyev had. By the time the premiere rolled around the ballet was hotly anticipated.

Fred cast Michael Somes as the Father of Armand, and choreographed our renunciation scene alone. When it was finished, Rudolf joined the rehearsal. As Michael and I played the scene over, an electrical storm of emotion built up in the studio. We came to the end, and Rudolf tore into his entrance and the following pas de deux with a passion more real than life itself, generating one of those fantastic moments when a rehearsal becomes a burning performance.

Margot Fonteyn, Autobiography, p.215

The anticipation built to the point where the first performance of the ballet was deemed an ‘event’, no doubt helped by the growing fame of the Fonteyn-Nureyev partnership. It was also the evening of the annual Royal Ballet Benevolent Fund Gala. Then editor of The Stage Eric Johns described the ballet as ‘tailor-made for two blazing ballet personalities’ (14th March 1963), but this was more the case for Fonteyn than it was for Nureyev. The nature of the ballet, as with all the adaptations, is that Marguerite/Camille will be more fleshed out than Armand, because the ballet is usually created for the ballerina, not the danseur. Fonteyn had been working with Ashton for around 30 years, and this ballet was the ultimate culmination of their work together.

Marguerite and Armand became associated with Fonteyn and Nureyev, and for many years they were the only dancers to perform the titular roles. A feature in The Tatler the date after the Gala premiered mentioned that tickets for upcoming performances were ‘strictly black market’ – a bit of an exaggeration, but one that shows how the fever has swept the ballet-going public. And this wasn’t just in London. The ballet was presented on foreign tours by the company, as well as on Fonteyn and Nureyev’s own tours. Royal Ballet dancer Leslie Edwards staged the ballet for the pair in countries such as Italy and Argentina, and the exclusivity of these performances cemented the ballet as Fonteyn and Nureyev’s.

A Royal Ballet revival was staged in 2000 for guest artists Sylvie Guillem and Nicolas Le Riche (or Royal Ballet principal Jonathan Cope). One newspaper jokingly described the revival dancers as ‘interlopers’, and reading the reviews it becomes clear that for many it was still Fonteyn and Nureyev’s ballet. There’s still some of that sentiment today, but since the first revival the work has also been taken into the repertories of companies like the Paris Opera Ballet, the Sarasota Ballet, the San Fransisco Ballet, and the Australian Ballet. Marguerite and Armand has held up as a moving work, but is still propelled forward by the leading dancers, especially Marguerite.

Die Kameliendame (1978)

Choreographer: John Neumeier

Music: Frédéric Chopin

Company Created For: Stuttgart Ballet

Decor: Jürgen Rose

Premiere: 4th November 1978, Württembergische Staatstheater Stuttgart, Germany

Length: 3-Acts

The last ballet I will write about is perhaps the one that deviates from Dumas fils’ original work the most. Through the introduction a ballet-within-a-ballet Neumeier pairs the characters of Marguerite Gautier and Manon Lescaut. He found the complexity of the novel fascinating, and utilised the fragmentary narrative to merge two stories together. In Manon Marguerite sees herself.

The role of Marguerite was created on Marcia Haydée, who at the time was both principal ballerina and director of the Stuttgart Ballet. Egon Madsen danced Armand, with Birgit Keil and Richard Cragun dancing Manon and Des Grieux respectively. Like Ashton, Neumeier considered the Sauguet score, but instead decided to use the music of Frédéric Chopin.

Since its premiere Die Kameliendame has been regularly danced by companies across the world, including the Hamburg Ballet, the Paris Opera Ballet, the Bolshoi Ballet, the American Ballet Theatre and the Vienna State Ballet. A filmed recording of the ballet was made by the Hamburg Ballet in 1987 with Marcia Haydée as Marguerite and Ivan Liška as Armand, and stage productions of the work have been recorded since.

Like with all the ballets, the role of Marguerite has become a showcase for dramatic ballerinas, which truly shows the riches that have come from adapting Dumas fils’ novel.

Sources

Chujoy, A. (1982). The New York City Ballet: the first twenty years. Da Capo Press.

Denby, E. (1986). Dance Writings. Dance Books.

Dolin, A. (1953). Alicia Markova: Her life and art. Hermitage House.

Fonteyn, M. (1976). Margot Fonteyn: autobiography. Alfred A. Knopf.

Garcia-Márquez, V. (1990). The Ballets Russes: Colonel de Basil’s Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo, 1932-1952. Alfred A. Knopf.

Guest, I. (2006). The Paris Opera Ballet. Dance Books.

Reynolds, N. (1977). Repertory in review: 40 years of the New York City Ballet. Dial Press.

Vaughan, D. (1999). Frederick Ashton and his ballets (Revised Edition). Dance Books.

Frederick Ashton Foundation Page on Marguerite and Armand: http://www.frederickashton.org.uk/marguerite.html

New York City Ballet Repertory Page on Tudor’s Lady of the Camellias: https://www.nycballet.com/discover/ballet-repertory/lady-of-the-camellias/

Royal Opera House Collections Page on Marguerite and Armand: https://www.rohcollections.org.uk/work.aspx?work=395&row=7&letter=M&genre=Ballet&