Flight on stage has traditionally been portrayed by actors on wires. From Peter Pan to Billy Elliot, these wires help take theatre beyond the stage, quite literally. So it’s no surprise that they’ve been utilised in ballet. And one of the oldest ballets, if not the oldest, we know to have used wires, is 1796’s Flore et Zéphire.

Charles-Louis Didelot

Charles-Louis Didelot was born in Stockholm in 1767. His Father, Charles Didelot, was maître de danse to the King of Sweden. As a child, Didelot used to accompany his Father to the lessons he gave, copying the dancers. His dance education really took off when he was sent to study with Louis Froussard, who, at the time, was the premier danseur of the Swedish Royal Ballet.

From there, he was sent to Paris, to study with the top teachers of the time. Among them was Jean Dauberval, known today for being the original choreographer of La fille mal gardée (you can read my blog post about Dauberval here). After Dauberval left Paris, Didelot studied with Jean-Barthélemy Lany and Jacques-Francois Deshayes, the father of dancer André-Jean-Jacques Deshayes.

As a dancer, Didelot performed across Western Europe. He was employed as a premier danseur of the Paris Opera Ballet from 1791-1794. He also danced in Sweden and London. But his success as a dancer would be overtaken by his success as a choreographer and a ballet master.

His first choreographic works, small pas, were produced upon his return to Sweden from Paris, when he was still a teenager. His choreographic prowess grew and grew, fostered by talents like Jean-Georges Noverre, the celebrated writer of Lettres sur la danse, et sur les ballets. Didelot was employed by Noverre in London.

In 1801 Didelot travelled to Saint Petersburg, the home of the Imperial Ballet. At the time the principal choreographer was Charles Le Picq, who was advancing Russian ballet and laying the foundations for the work of Didelot. Didelot would be a premier danseur of the troupe until 1806, when a leg injury ended his dancing career. But after this he’d still choreograph and teach, and even before his injury he was creating spectacles for the Imperial Ballet. Like a lot of ballets of the time, he drew on myths and legends for topics, using fauns, dryads, cupids and gods.

He left Russia for the first time in 1811, with the intent to go to Paris, which, at the time, was the centre of ballet. To have your ballets produced at the Opera was the ultimate honour, and Didelot was hoping he could stage his masterpiece of flight. On the way to Paris he was involved in a shipwreck, losing most of his music and choreographic notes. He eventually made his way to London; he wouldn’t stage his ballet in Paris until 1815 (more on that later).

He returned to Russia in 1816, following the Napoleonic Wars, and took up the post of maître de ballet. He produced over 20 ballets during his time there, and those are the ones we know of. He most certainly choreographed smaller pas, and played a huge part in the development of Russian ballet, most notably improving the standard of the corps de ballet through both his teaching and his choreography.

He resigned from his role around 1829, after a dispute with the Director of the Imperial Theatres, Prince Sergei Sergeevich Gagarin (1795-1852). Gagarin thought an interval was taking too long, and sent word for the set and costume changes to be sped up. Didelot ignored this message, which infuriated Gagarin, who threatened him with arrest. Didelot handed in his resignation the next day.

He stayed in Saint Petersburg after his resignation, but his glory days as a choreographer were behind him. The ballet in Russia (following the French) had moved from classical myths to sylphs and fairies, as Romanticism took hold. In 1837 he left for the Crimean peninsula, in order to try and improve his health, but he didn’t get there, and he passed away in Kiev in November of that year.

Defying Gravity

Flore et Zéphire premiered at the King’s Theatre in London on the 7th July 1796. Today this theatre is known as Her Majesty’s Theatre, and at the time it’s ballet troupe was rather renowned. We know most about ballet there during the romantic era, when the like of Marie Taglioni, Fanny Elssler, Carlotta Grisi, Lucile Grahn and Fanny Cerrito appeared at the theatre.

The original music for the ballet was composed by Cesare Bossi (1773-1802) who wrote a lot of music for ballets produced at the theatre, including other ballets by Didelot. The machinery and design was done by Liparotti, though not much is known about him.

Zephyr was danced by Didelot himself, and his wife danced the role of Flore. Rose-Marie Pole (most commonly known as Madame Rose), Didelot’s first wife, was a dancer at the Paris Opera from 1786-1793. They had a son together, Charles (1801-1855), and she danced alongside Didelot in London and Saint Petersburg. She passed away around 1803. His second wife was Maria Rosa Colinette (1784-1843), another ballerina.

Other dancers in the ballet included Mademoiselle Hilligsberg; Mademoiselles Parisot and Bossi; Monsieur Menage; Mademoiselle Hill, and a corps of shepherds and shepherdesses. There were most likely other soloist roles featured in the ballet as well.

Mademoiselle Hilligsberg (her full name was most likely Marie-Louise Hilligsberg) was born around 1765-1770, and had trained under Gaétan Vestris (1729-1808), father of celebrated dancer Auguste Vestris (1760-1842). Her younger sister Janet was also a dancer, but as far as we know she was not as present at the King’s Theatre as Hilligsberg the elder, so the elder is most likely our dancer. She joined the King’s Theatre in 1787, becoming a celebrated soloist during the 1790s, before retiring and moving to France around 1803. She was particularly known for dancing trouser roles. She died in 1804.

The Menage family were a theatrical family of London. The member of the family we know the most about is Arabella Menage (1782-1817), who married painter Michael William Sharp. My source for the cast, Cyril W. Beaumont’s Complete Book of Ballets, does not list the first name of this dancer. We do know, however, that Arabella was taught by Didelot, so it is most definitely this family. As such, the most likely culprits are Monsieur Menage the elder (fl.1775-1803), who danced at Drury Lane, or his son, Frederick Menage (1788-1822), who started his career as a child soloist dancer around 1792. Frederick and Arabella’s sister Mary (1778-1830) was also employed at the King’s Theatre in 1796, so it’s possible she danced in the ballet too.

Mademoiselle Parisot (born c.1778) had danced in Rouen and Paris before making her way to London in 1796. She danced at the King’s Theatre and Drury Lane, and starred in some of Didelot’s other ballets. She was known for extending her legs higher than was the norm when doing steps like arabesques. A sketch by caricaturist Richard Newton shows Parisot dancing with her ‘scandalous’ leg extension, while being ogled at by two men. She left the stage around 1807, marrying a Mr Hughes.

Hill is a very common surname in England, and we know barely anything about our Mademoiselle Hill. She played a Little Cupid in the ballet, so it’s plausible that she was a child. Mentions of this Mademoiselle Hill don’t list any other roles; it could be that she never danced again, or that she didn’t grow up to be a noted soloist dancer. Either way, pretty much all we know ahout her is that she was in Flore et Zéphire.

Mademoiselle Bossi married the composer Cesare Bossi in 1786, and she had only just began to be billed under her married name. Before that she used her maiden name Mademoiselle Del Caro, having arrived in London with her sister in 1794. She was widowed after Cesare’s death in 1802. She retired from the stage the following year.

Subsequent Flights

Flore et Zéphire is undoubtedly Didelot’s most well-known ballet today, but it was also his most popular during his own time as well.

Didelot and Rose (the 1st wife) reprised their roles at the Hermitage Theatre in 1804. The Hermitage theatre is one of the theatres in the Winter Palace complex in Saint Petersburg, which today houses the Hermitage Museum, but at the time was the official residence of the Tsar.

Another revival was mounted at the Hermitage in 1808. For this revival, the music was changed, a new score being composed by Catterino Cavos. The name was also changed to Zephyre et Flore. The role of Zephyr was taken by Louis-Antoine Duport (1786-1853) who came to Russia that year after leaving the Paris Opera. Marie Danilova (1793-1810) danced Flore.

This revival was noted for the ballerinas appearing briefly sur les pointes. While it is unknown whether Danilova was the first to dance it in this way, contemporary reports show that this ballet was indeed an early proponent of pointe work, and this reflects on another ballerina, who made her London debut in this role.

After returning to Western Europe Didelot staged the ballet in London at the Royal Opera House (in 1812), but he had his sights set on Paris. At the time the maître de ballet at the Paris Opera was Pierre Gardel. While he was an experienced dancers and choreographer, he was known for ruling the ballet like it was an absolute monarchy, aiming to keep other choreographers from producing works for ‘his’ company. Tensions between him and Louis-Antoine Duport had driven Duport to resign and leave for Russia, and with his experience, Didelot posed a threat to Gardel’s Napoleonic reign.

It was in 1815 that Didelot got to stage Flore et Zéphire in Paris, but only on the condition that he would pay the costs. They had deemed the ballet too expensive to mount, and said all the expenses must be paid by Didelot. He was offended, but agreed.

The rehearsal period was rather stressful, and Didelot was considering abandoning the project and leaving. He stayed in the end, and the ballet was a success. At the premiere on December 12th King Louis XVIII was in attendance, and was so pleased by the ballet he called Didelot to his box, giving him a large monetary gift of 2,000 francs.

The music for this revival was by Frederick Venua (1788-1872). Venua has no other known credits at the Paris Opera, and his score originates with the 1812 London revival. He rescored music for many of Didelot’s ballets, most likely because of the shipwreck Didelot was involved in. It would be used in the 1830 London revival.

Zephyr was danced by Monsieur Albert (1789-1865). Albert was the leading danseur noble of the company at the time. The Journal des débats on the 14th December reports: ‘no other dancer is worthier than he to represent that God whom poets invest with all the graces of youth and beauty’. Opposite him was Geneviève Gosselin (1971-1818) as Flore, who again, appeared en pointe.

The same reviewer in the Journal des débats noted that the flight seems were more impressive and fantastical than any seen at the Opera before. They were also impressed with both the dancing of Geneviève and one of her younger sisters, who danced the dual-role of Venus and a shepherdess, as well as Mademoiselle Delisle, who danced a Bacchanale.

While the ballet was well-received, Didelot received a check for 2,400 francs. So after being gifted 2,000, he now owed the Opera money. He paid the money, but left Paris, becoming jaded by his experiences.

A student of Didelot, Adam Pavlovich Glushkovsky (1793-c.1870) staged the ballet at the Mokhovaya Theatre. This was a short-lasting (1806-1824) theatre in Pashkov House in Moscow, which today houses the Russian State Library. Glushkovsky had been transferred to Moscow from Saint Petersburg, and began to both build the Moscow ballet and stage the Saint Petersburg repertoire there. Naturally this included ballets by Didelot, but the score by Venua was used. T.I. Glushkovskaya, Glushkovsky’s wife, danced Flora.

The following year Didelot staged a new production at the Hermitage Theatre, with scenery by S.P. Kondratiev and costumes by K. Babini. A decade later Avdotia Ilinichna Istomina (as Flore) led a revival at the Bolshoi Theatre of Saint Petersburg, using the second score by Catterino Cavos. Istomina was the leading dancer of the Imperial Ballet during the 1820s, and was described by Alexander Pushkin in his poem Eugene Onegin.

Forth from the crown of nymphs surrounding, Istomina the nimbly-bounding. With one foot resting on its tip, slow circling round its fellow swings, and now she skips and now she springs, like down from Ælouis’s lip, now her lithe form she arches o’er, and beats with rapid foot the floor.

Eugene Onegin, Alexander Pushkin, translated by Lt.-Col. Henry Spalding, 1881

In 1829 the Bolshoi Theatre of Moscow (the well-known one that today houses the Bolshoi Ballet) used Cavos’ score in their staging. Another composer, N.E. Kubishta is credited, so it’s likely additional music was composed. Félicité Huller-Sor (c.1805-1874) danced Flore.

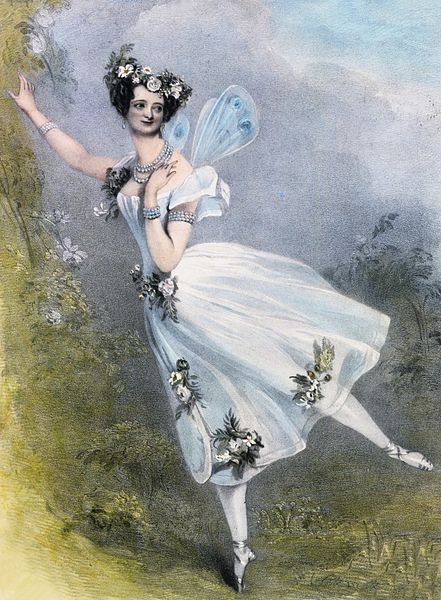

London staged the ballet in 1830, in a production by Filippo Taglioni, for the London debut of his daughter, Marie. Filippo was well-known for tweaking choreography to suit Marie’s talents, which likely happened in this case. The music used was the score by Frederick Venua.

Taglioni debuted in the role on the 3rd June 1830, and a review in The Times the following day notes that she ‘met with a most favourable reception, and received and deserved great applause throughout her dancing’. Taglioni became the greatest of her time, and it’s easy to see how the influence the pointe and flight work of this ballet may’ve inspired later works.

The last big revival we know of was in 1841 at the Bolshoi Theatre of Saint Petersburg. As Didelot had passed away, the choreographic aspect of the ballet changed, being reworked by Antoine Titus (c.1780-c.1860), who had come to Saint Petersburg in the 1830s. A Kuzmina is also credited; if this credit is true it may be referring to Lyubov Kuzmina, an 1835 graduate of the Imperial School. Zephyr was danced by Emile Gredlu. Gredlu had arrived in Saint Petersburg around 1834, and would later become a great teacher at the Imperial School.

So why is it forgotten?

In this series we’ve looked at ballets that were forgotten because they weren’t very good (La Chatte, Les Mohicans), and ballets that were celebrated at the time, but their time eventually passed (Fiammetta). Flore et Zéphire falls into the second category.

Didelot continued to use flight in his ballets, training his corps in Russia to achieve this effect with wonderful precision. This effect made his ballets a spectacle, bringing in punters even if the scenario of the ballet wasn’t too sophisticated.

Marie Taglioni’s stint in the ballet could be said to have provided the foundations for La Sylphide (1832). La Sylphide burst open the door for the romantic ballet, and the magic of the Sylph has endured all the way into the 21st century. As we saw with Didelot’s ballets in Russia, when romanticism took hold gods and fauns were cast aside.

Perhaps the biggest contribution of Flore et Zéphire to ballet as a whole is the dancing sur les pointes. This effect is supposed to have been achieved by the ballerina quickly posing on the tip of her toe at the same time the flight machine took her weight. Filippo Taglioni would push this effect when choreographing for his daughter Marie. Marie Taglioni is said to be the first dancer (or the trendsetter) for truly dancing en pointe. It’s hard to believe ballet didn’t always include this defining aspect, but it did.

Sources

Beaumont, Cyril W. (1956). The Complete Book of Ballets. Putnam, London, England.

Beaumont, Cyril W. (2020 reprint). A History of Ballet in Russia. Noverre Press, Hampshire, England.

Guest, Ivor (2006). The Paris Opera Ballet. Dance Books, Alton, England.

Guest, Ivor (1966). The Romantic Ballet in Paris. Pitman and Sons, London, England.

Highfill, Philip H., Burnim, Kalman A. and Langhans, Edward A. (1984). A biographical dictionary of actors, actresses, musicians, dancers, managers & other stage personnel in London, 1660-1800. Volumes 7, 10 & 11. Southern Illinois University Press, USA.

Thank you so much for this wonderful insight into the early days of ballet. I really enjoyed reading this article.

LikeLiked by 1 person