In 1948 Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger released the film The Red Shoes, in which Moira Shearer stars as Vicky Page. Page is a ballerina and during the film takes part in The Ballet of the Red Shoes. The movie was critically acclaimed, and was the basis for both a 1993 Broadway musical and a 2016 New Adventures ballet. However, before The Red Shoes was a ballet, a musical, or a ballet within a film, it was a ballet. In 1898.

Now the 1898 ballet titled The Red Shoes was not based on the Powell and Pressburger film, as you can probably guess. They both took inspiration from the Danish author Hans Christian Andersen, and his 1845 story De røde sko. In the story Karen’s Red Shoes condemn her to a life of dancing. Karen became Vicky Page in 1948, and in 1898 she was Darinka, a Russian peasant girl.

In my last blog post I looked at ballet at London’s Alhambra Theatre, and this ballet was another Alhambra production. If you are interested in more of a background of the theatre, I recommended reading that post either before or after this one.

Die roten Schuhe

When I said The Red Shoes was an Alhambra production, I did sort-of lie. The ballet originated in Vienna, where it was first performed on 18th August 1898 under the German name for the fairytale, Die roten Schuhe. This performance took place at the Wiener Hofoper (Vienna Court Opera), today’s Wiener Staatoper (Vienna State Opera).

This ballet was choregraphed by Josef Haßreiter (1845-1940), who by that point had been the Maître de ballet at the court for some time. His first big choreographic success was Die Puppenfee (1888), a story of toys in a toyshop who come to life. This ballet was later performed in Russia in a production choreographed by Nikolai and Sergei Legat, and the plot was similar to Léonide Massine’s La Boutique fantasque (1919). Die Puppenfee was one of the most successful ballets in the German-speaking world, enjoying many performances in multiple countries.

A frequent collaborator of Haßreiter was Hermann Heinrich Regel, and the pair co-wrote the libretto for Die roten Schuhe. The music was done by a Hungarian composer, Raoul Maria Mader (known in Hungarian as Rezső Máder). Máder primarily worked in Budapest, but has credits for multiple Vienna ballets in the 1890s, which is unsurprising when you consider that both countries were united as Austria-Hungary at the time.

Haßreiter continued to choreograph ballets into the 1910s, most of them premiering at the Hofoper. Die roten Schuhe was highly successful, remaining in the repertory at the Hofoper until 1922. The last recorded performance for the ballet was on the 2nd February 1922, by which point the ballet had received about 80 performances.

There’s also evidence that the ballet was produced elsewhere in Germany. Volume 84 (1900) of the “Über land und Meer” (Over Land and Sea) magazine notes that the ballet was to be produced at the Königliche Oper, which is today’s Berlin State Opera. The production carried over the libretto and score from the Vienna production.

Not long after the ballet’s premiere the Alhambra acquired permission to use Haßreiter and Regel’s libretto and Màder’s score for a production of their own. This ballet would not be choreographed by Haßreiter, and would instead be choreographed by the Alhambra’s resident choreographer. And in true Alhambra fashion, their resident choreographer was Italian.

The Red Shoes

Ballet in Britain at the time could not be called home-grown. While there definitely were British dancers, and British choreographers, many of the big ballet theatres imported talent from mainland Europe. The Alhambra’s newly-appointed resident choreographer was Giovanni Pratesi, who had succeeded fellow Italian Carlo Coppi in 1898. The Empire Theatre, the Alhambra’s biggest rival, employed the Vienna-born Katti Lanner.

Pratesi had an extremely short tenure at the Alhambra, only working there from 1898 to 1899. He was primarily a mime, having performed in ballets in Italy, and pantomime sketches in France, Spain and London. His Father, Fernando Pratesi, had been a dancer and choreographer, and his mother Filomena was a mime. The Red Shoes would be one of only 5 known ballets he choreographed for the Alhambra, those being: Jack Ashore, The Red Shoes, A Day Off, Napoli and Soldiers of the Queen. Of these, The Red Shoes was the least successful, only lasting 28 weeks in the repertory before being dropped.

As noted, the libretto used was Haßreiter and Regel’s, and the score was Màder’s, but the Alhambra did make changes. Their Music Director and in-house composer, George W. Byng, received credit for parts of the score. The Era (14th January 1899) notes that the music and scenario was ‘nearly identical’ to the Vienna production, but that the choreography and costumes were entirely new. Contemporary adverts for the ballet show that Byng composed choral music (the Alhambra had their own choir, and at this time were enjoying using them wherever they could). He also composed the ‘fantastic dance’ in the second of the five scenes.

The costumes were designed by J. Howell Russell. Russell had been designing for the Alhambra since 1880, and had also worked in America in the early 1890s. Costume making fell to Charles Alias, the Alhambra’s usual costume maker. Another Alhambra regular, Philip Howden, handled the scenery, but a Schallud was also credited. This may’ve been the scenic designer in Vienna.

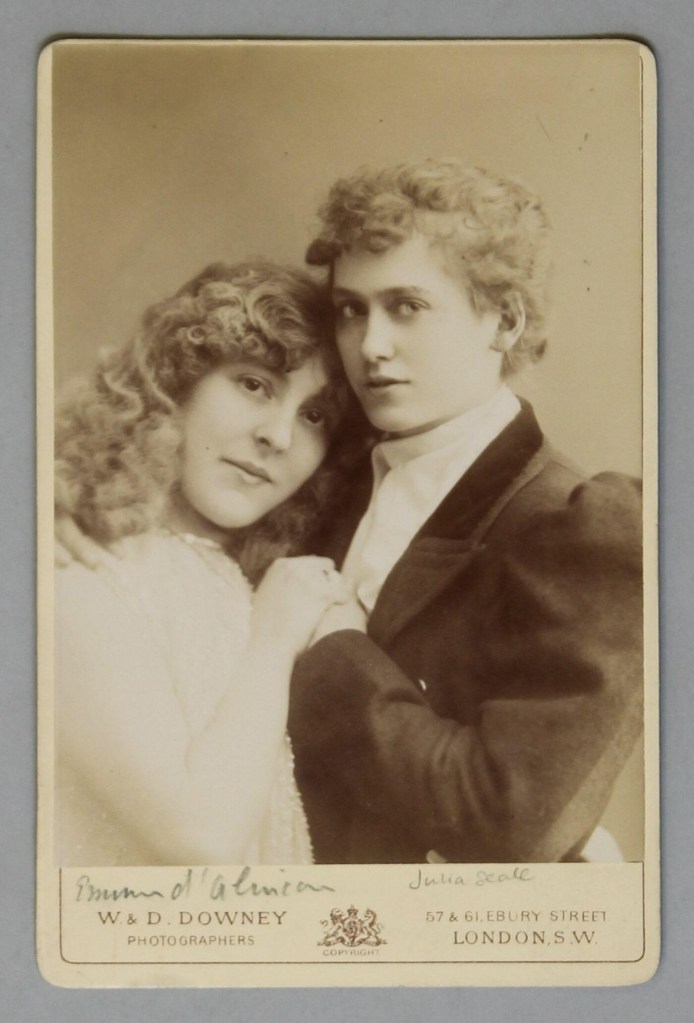

The ballet premiered on Monday 30th January 1899, but seems to have been pushed back. The Morning Post (Monday 2nd January) features a short article on the Alhambra’s programme that evening, which is said to include the premiere of The Red Shoes. Similarly, The Referee (Sunday 8th January) notes that the ‘long-talked of’ ballet was now to premiere on the 30th January instead of its original premiere date. No official reason is given for the pushback, but the St James Gazette (Friday 13th January) notes that one of the performers, Emillienne d’Alençon, had not arrived in London yet, so it was probably due to scheduling conflicts.

Emillienne d’Alençon was to portray both the Angel of Justice and the Angel of Mercy, and this was to be her debut in England. The Pall Mall Gazette (14th January) quite bluntly notes that to call d’Alençon a ‘famous dancer’ would be setting her up to fail, and that she was ‘first and foremost a beauty’. She had appeared at L’Olympia in Paris in a spectacle called Nero, in which, as the Gazette puts it, ‘she did not dance, she did not act’. She ‘merely posed’. Her parts were only small parts, but they allowed to English audiences to admire her beauty.

The heroine, Darinka, was danced by Josephine Casaboni, an Alhambra regular. The Morning Post (Tuesday 31st January) calls her performance the triumph of the night. Julia Seale was also praised in the role of the Spirit of Temptation; she was another Alhambra regular who had been with the company for almost a decade at this point. Though the Alhambra ballets had traditionally featured male roles played by females en travesti, this was changing. Mr Lytton Grey danced Gregor, Darinka’s sweetheart. Grey had been at the Alhambra for half a decade.

Another significant part was taken by Charles Raymond, who danced Father Fedor, Darinka’s Father. Fritz Rimina (or Rimma) danced Ivan, a wealthy man who attempts to woo Darinka. G. Almonti portrayed a Veteran, while W. Almonti portrayed a Clown. A character described as a ‘Quack Doctor’ was danced by a Mr Artelli.

There does appear to have been a few en travesti roles, as Miss Richmond was credited as Valdimir, Miss Villis as Nicolas, Miss A. Vivian as Vasilovitch and Miss Peverell as Muravieff. Miss B. Ford danced a character named Catherine, and Miss A. Edwards a Lydia, though their roles are not described further. Ada Taylor, Miss A. Houghton, Leonie Roy and Rose Batchelor danced a Circassian dance.

On the evening of 30th January the programme featured another Pratesi ballet, Jack Ashore, a ‘Boy Juggler’, Bicycle Polo, Walton’s Monkeys, Mademoiselle Orbasany’s Cockatoos, and the evening finished with Mademoiselle Erna’s Dogs. The Red Shoes came in the middle of all these acts, beginning at 10:05 and running for 50 minutes. The house was crowded, and they heartily applauded the new ballet.

Reviews of the ballet show that it was hardly a traditional Alhambra spectacle. The ballet was generally described as realistic, while Alhambra ballets were known for their grandeur. The work of the corps de ballet was highly praised, as was the scenery and costumes.

The ballet was performed up until August 1899. The Daily Telegraph (Tuesday 8th August) notes the ballet had been withdrawn, and the next new ballet, Napoli, would premiere on the 21st August. Preserved articles from that month show authors lamenting the loss but being excited for the new ballet, in which Casaboni, Grey, and Pratesi himself would dance leading roles.

Le scarpette rosse

Darinka had danced her way into success in Vienna, and in London. In 1900, she conquered Milan. Achille Coppini (1846-1912) produced the ballet at La Scala, Italy’s most famous opera house. I don’t know Italian, and as such I know a lot less about this production.

The production retained the libretto and music of the Vienna production, though was choreographed by Coppini. A dancer named Giuseppe Rossi was credited in the role of an ‘Invalido’, or an invalid person. This character may correspond to the ‘Veteran’ character in the London production.

Pratesi returned to Italy after his stint at the Alhambra, stopping in Paris along the way. He debuted as a choreographer at La Scala in 1904, reviving his production of Napoli in 1906. From what I can find his production of The Red Shoes did not live on following the London performances.

Legacy

The 1898 ballet has been eclipsed by the success of later adaptations, but I think it serves as an interesting look into how theatre productions spread across countries. The Red Shoes premiered in Britain less than half a year after the ballet’s premiere in Vienna, an astounding turnaround time.

It’s also an interesting production for the Alhambra. During the 1890s their balletic offerings included Aladdin, Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, and Beauty and the Beast, but inspiration in the next decade would come from the history of Paris, a political agreement, and women who smoked (you can read my last post if interested in those stories). The Alhambra’s corps de ballet would eventually be dismissed in 1912, with The Red Shoes being the company’s last proper fairytale ballet.

Secondary Sources

Beaumont, C.W. (1956). The complete book of ballets. Pitman.

Guest, Ivor. (1992). Ballet in Leicester Square. Dance Books.

Matsumoto, Naomi. (2017). Giovanni Vittorio Rosi’s Musical Theatre: Opera, Operetta and the Westernisation of Modern Japan. In Musical Theatre in Europe 1830-1945.

Scadafi, N., Zambon, R. & Albano, R. (1998). La Danza in Italia. Gremese.

Schedule of the Vienna Opera 1869-1955 database listing for Die roten Schuhe: https://www.mdw.ac.at/imi/operapolitics/spielplan-wiener-oper/web/opus/422